From “¡Patria o muerte!” to “El rincón de la paciencia”: Reading the Cuban Nation in Time in Memorias del subdesarrollo, Fresa y chocolate, and Suite Habana

Rachel Ellis Neyra, PhD., University of Pennsylvania

1. Apocalypse, Nationalism, and Contradictions of Desire

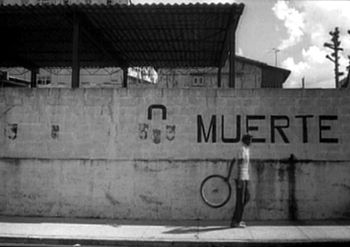

As the ominous sense of the October Missile Crisis intensifies towards the end of Tomás Gutiérrez Alea’s iconic film, Memorias del subdesarrollo(1968), there is a fleeting frame in which “Patria o”has been painted over on a wall, and all that is left is the word, “muerte” (1.27.22). Walking along the wall and through the middle length shot is a black man holding a  bicycle tire. His face turns to the camera as he carries on with tire in hand, while Charles Mingus, the genius African American jazz bassist and pianist, trails off from singing an extra-diegetic musical snippet – “Oh Lord, don’t let them drop that atomic bomb on me!” – from one of the songs on his 1962 album, “Oh Yeah.” The final scenes of Memorias del subdesarrollo intensify ambiguity rather than pretending to resolve it, about Cuba’s relation to the US, the USSR, and the notion of “underdevelopment” – so, to the processes of psychic, social, and economic decolonization amidst Revolution’s dance with “development.”(1)

bicycle tire. His face turns to the camera as he carries on with tire in hand, while Charles Mingus, the genius African American jazz bassist and pianist, trails off from singing an extra-diegetic musical snippet – “Oh Lord, don’t let them drop that atomic bomb on me!” – from one of the songs on his 1962 album, “Oh Yeah.” The final scenes of Memorias del subdesarrollo intensify ambiguity rather than pretending to resolve it, about Cuba’s relation to the US, the USSR, and the notion of “underdevelopment” – so, to the processes of psychic, social, and economic decolonization amidst Revolution’s dance with “development.”(1)

Reiterated in the final scenes of Memorias del subdesarrollo (Mds) that inscribe ambiguity are images that also signify the temptation of apocalypse, one that arguably accompanies the equipment of national-territorial sovereignty: tanks in the streets of Havana, tearing up space in which they don’t quite fit – urban planning does not happen with their dimensions in mind (1.27.33; 1.30.39; 1.32.01); Fidel Castro on television declaring no fear in the face of threats to Cuban sovereignty, but instead a need to learn to “…vivir en la época en que nos ha tocado a vivir,” and concluding his speech with a resounding, “¡Patria o muerte! ¡Venceremos!” (1.27.49-1.28.47); automatic weapons being threaded up the side of a building for soldiers perched on the roof (1.31.27); anxiety on the bodies of subjects, as gestured in the final shots of the character Sergio whose pacing throughout his apartment is interrupted by a dialectic of shots of the tanks in the street and the paintings on his walls, such as that of a beheaded youth and an angel holding a sword (1.30.24). And all of this laced with the minimal yet stalking musical score of Leo Brouwer. While recalling the views of Sergio as a “useless intellectual,” as critic Deborah Shaw pegs him, and “nothing,” as the character Elena calls him, we see the elements of existential angst that are explicit in Edmundo Desnoes’ novel cling with subtlety to the cinematic Sergio: burping at breakfast; yawning gratuitously on his balcony; scratching his armpits; fantasizing about sex with his maid, Noemí; and pacing unshaven at the close of the film. These images focus viewers on a body caught by contradictory desires about the self, the nation, and apocalypse.

The film’s final movements between the apocalyptic and uncertain are prompted when Sergio scoops up the 22 October 1962 edition of Revolución slid beneath his apartment door (1.24.01). Rendering Sergio’s gaze in first person, the camera first focuses on the most dominant front-page headlines: Preparativos de agresión yanqui. Más Aviones y Barcos…; then it zooms in: Inesperado regreso de Kennedy a Washington…Un Ambiente De Histeria Belica (1.24.10). With no break to Sergio’s face, the camera jumps to other headlines, as, perhaps, would the average reader: a young mother having given birth to triplets is followed by word of a Russian dog named “Grishka” who has two hearts – excess or miracles?; other snippets, including Palabras de Mao Tse Tung, which condemn Administrative violence as a solution to ideological problems; a brief complaint about an unsafe balcony that has not been fixed by La Reforma Urbana. The cartoon of Salomon ends the newspaper sequence with a giant question mark crushing him on the head, and finally asserting sound – a Boing! – to interrupt the silent reading of these various headlines. However playfully, this crushing question mark brings the mind back to Sergio’s intellectual duplicity within the Revolution, and more, to the dangerous duplicities between the aforementioned nation-states at that moment in time. After being shown headlines that shift from the fatalistic to the uncertain, the film cuts to photographs of Noemí, the maid’s baptism, and a fantasy sequence of Sergio’s with her, interrupted by Kennedy’s voice on the radio on 22 October 1962 (one month and one year to the day of his assassination).(2) This sequence intensifies the reminder of embodiment, particularly in a situation where apocalyptic foreboding exists alongside uncertainty. In it, the camera’s attachment to snippets is notably less concerned with narrative continuity than placing fragments into contact.

The repetition of snippets in this scene of reading the newspaper presents what I call a metonymic mode of reading the nation that has more value than one looking for homogeneity, congruity, and wholeness. Two other instantiations in Mds that encourage a metonymic reading mode are the documentary footage that interlaces the Bay of Pigs invasion and subsequent trial into the film – again, less for narrative than tonal and stylistic value – and the scene of Sergio and Elena’s visit to the ICAIC office that leads to our viewing a sequence of unrelated censored scenes from the Batista era. Not narrative continuity, but an insistence on the importance of fragments and the power of the cinematic cut is presented in these scenes. But it is the shot sequence of the newspaper’s snippets that brings us into the final moments of tension in the film. Suspended in those last moments is a question that intensifies over time, becoming only more poignant in Fernando Pérez’s film, Suite Habana (2003): Homeland and what other than death?

While Antonio Benítez-Rojo reflected in the late 80s on the October Missile Crisis as the moment – curiously – that he “reached the age of reason” in the introduction to La isla que se repite (1992), and narrated having found an imaginary balm for apocalypse between the thighs of two old black Cuban women, it is, arguably, time that became a salve of sorts that he could apply in what he calls “re-readings” of the Caribbean (read: Cuba, et al). While a great deal of critical attention focuses on this book’s idiosyncratic mixture of postmodern and post-structural theories with the narrative prowess of a fiction writer, here we will look into the book’s introductory excursus as an attempt to mute the forces of apocalypse in the Caribbean, one that is ultimately unconvincing but rich for analysis.

In the twenty-nine-page introduction to the second edition (1996) of the English translation, The Repeating Island, Benítez-Rojo describes the Caribbean as a space that “sublimates apocalypse and violence” (16), or some variation on this expression of nonviolence as natural to Caribbean life, nearly twenty times. This goes so far that on page twenty-four as he begins to describe the Caribbean text through literature, he detours saying that literature is always “conflictive,” and so to exemplify a quintessential textual example of Caribbean “performance,” one of the book’s key terms, he will, instead, cite a “political performer” (because politics is not conflictive?): Martin Luther King. He says that “[h]is vehement condition as a dreamer” constitutes his Caribbean side and shows that Caribbean performance is not limited strictly by geography or language. But surely we can see that to invoke the iconic arbiter of resistance through nonviolence is more loaded than just that. Particularly since the minister was assassinated, and in the context of what progressive views of US History may call a Movement for Civil Rights, but others, such as that of James Baldwin, alternatively cite as the most recent slave uprising in US history (Baldwin 141).

Proceeding, this essay follows three basic lines of argument that entwine at different moments: first, a critique of The Repeating Island’s attempts to sublimate the importance of apocalypse in Cuban and Caribbean national-cultural expressions, which compels the thought, instead, that apocalypse is a decisive entanglement in Caribbean and Cuban history and aesthetics; second, an elaboration on the persistence of apocalyptic figures in the midst of contemporary anxieties about globalization and neo-colonialisms throughout the Caribbean, and specifically in Cuba; third, in arguing for a metonymic mode of reading, this essay proposes radical patience as an ample option to imagine the future through the Cuban nation’s fragments.

Metonymy is the substitution of a representative part for an intended whole, literally, a change of name inasmuch as what would seem small enlarges – what seems monadic belies plurality. In this discussion of cinema and nationalism, metonymy becomes an organizational mode of reading that works hand-in-hand with the operation of the cinematic cut (to be discussed). Metonymy, the cut, and repetition emphasize meaningful breaks in the social fabric, which reveal alternative ways of belonging to a place, particularly to one increasingly aware of itself as diasporic. It is in the reading of Suite Habana that these figures and a response to the question, Homeland and what other than death?, crystallize. But we will build a thoughtful entry into that section through the progression from Memorias del subdesarrollo (1968), to The Repeating Island(1992; 1996), to Fresa y chocolate(1993), and, finally, into Suite Habana (2003).

The Repeating Island’s (TRI) introduction argues that la flota, la encomienda, and the Plantation’s repetitions accumulated to become “the void,” “the swirling black hole of social violence” to which Caribbean textual performances may iteratively refer, but ultimately can sublimate. TRI presents the notion of Caribbean textual performance as a “carnivalesque catharsis that proposes to divert the excesses of violence” (22) right up to the final page of the introduction, where it underscores “the strongly feminine” and festive system of signs that are constitutive of a negotiable and “fluvial” Caribbean (29). But we run into a problem when it is argued that the Plantation is a Caribbean machine that persists in the present, “repeats” today throughout the Americas:

This machine, this extraordinary machine, exists today, that is, repeats itself continuously. It’s called: the plantation… I want to insist that Europeans finally controlled the construction, maintenance, technology, and proliferation of the plantation machines, especially those that produced sugar…[F]urthermore, it usually produced the Plantation, capitalized to indicate not just the presence of plantations but also the type of society that results from their use and abuse…[P]lantation machines turned out mercantile capitalism, industrial capitalism…they produced imperialism, wars, colonial blocs, rebellions, repressions, sugar islands, runaway slave settlements, air and naval bases, revolutions of all sorts, even a “free associated state” next to an unfree socialist state (8, 9).

The Plantation machine’s repetitions annul the idea that it is something frozen in the past, a site with no relation to today. Benítez-Rojo’s insistence on different forms of its repetition is one of the richest interventions of TRI. Indeed, the Plantation as system channeled outward and proliferated just as it changed form to constitute not only rural but also urban spaces throughout the Americas. So, if the slave codes, the color line, and the “Black Belt,” as it was called in the US American South, were carried into the very formations, designs, and boundaries of towns and cities, then how can these violences simply be sublimated? Is not the emphasis on the varied coexistences of Caribbean peoples not only about nonviolence, but also precisely about historical violences that exfoliate through aesthetic and cultural representations, and often to the benefit of the narratives of nationalism in the modern period? The modern being that to which TRI alludes hastily in the last sentence above (rebellions become revolutions which lead to different geopolitical outcomes), but in general avoids, defers for discussion of the premodern, religious, historiographic, and then the postmodern (de la Campa 100-103)?

In this context, the specific passage on the impossibility of Caribbean apocalyptic desire is on the first level a subtle deferral of the Cuban Revolution as authentic, but the stakes go higher. On a second level, this marks a broader slip in this text’s imaginary of the Caribbean. With Mds’s finalscenes that intensify the anxiety of apocalypse fresh in our minds, let’s revisit TRI’s terms that attempt to disarm the scene of apocalypse in Havana in October of 1962:

of the Cuban Revolution as authentic, but the stakes go higher. On a second level, this marks a broader slip in this text’s imaginary of the Caribbean. With Mds’s finalscenes that intensify the anxiety of apocalypse fresh in our minds, let’s revisit TRI’s terms that attempt to disarm the scene of apocalypse in Havana in October of 1962:

I can isolate with frightening exactitude – like the hero of Sartre’s novel – the moment at which I reached the age of reason. It was a stunning October afternoon, years ago, when the atomization of the meta-archipelago under the dread umbrella of nuclear catastrophe seemed imminent…While the state bureaucracy searched for news off the shortwave or hid behind official speeches and communiqués, two old black women passed “in a certain kind of way” beneath my balcony. I cannot describe this “certain kind of way”; I will say only that there was a kind of ancient and golden powder between their gnarled legs, a scent of basil and mint in their dress, a symbolic, ritual wisdom in their gesture and their gay chatter. I knew then at once that there would be no apocalypse… for the simple reason that the Caribbean is not an apocalyptic world; it is not a phallic world in pursuit of vertical desires of ejaculation and castration. The notion of apocalypse is not important within the culture of the Caribbean (10).

Whereas bureaucracy looks for official news of imminent death, the artist sees culture in an unnamable but otherwise polyrhythmic walk. He continues and notes that the “atomic projectiles” lodged in Cuba for a spell belonged to a “Russian machine” that was terrestrial, of the steppe and a long cultural forgetting of the sea. Whereas the Caribbean “is not terrestrial but aquatic, a sinuous culture where time unfolds irregularly and resists being captured by the cycles of clock and calendar. The Caribbean is the natural and indispensable realm of marine currents, of waves, of folds and double-folds, of fluidity and sinuosity” (11).

It is a long-standing European and US American colonial, imperial, and touristic trope to render the Caribbean as a space outside of Time, outside of History, perpetually under the sun, and if it were not for machetes, filled with ironically redundantly bursting vegetation. Caribbean time is not irregular, as Benítez-Rojo writes above, but it does present an alternative logic to the idea of four distinctive seasons and the accompanying aversions to repetition of Western European paradigms (Snead). There is not an analogous aversion to repetition in Caribbean culture and philosophy – its musical forms may be the most familiar examples to note, though we will look later at the micro-movements and quotidian practices of Pérez’s film, Suite Habana, as instantiations of repetition’s value.

While the rhetorical posture being struck in the passage above is that the old black women’s bodies are sites of an elusive knowledge, and this is what constitutes the speaker’s relation to “reason,” the language here, and in other places of the introduction, becomes reductive of the feminine to the fluvial, mysterious, and festive. One cannot argue with the significations of different manifestations of carnival, dance, and oral expressions as constitutive of Caribbean aesthetic, cultural, and philosophical forms (Glissant; Henry). But I would argue that these are also expressions of a dangerous poiesis, a revolutionary desire to overturn historical modes of colonial-imperial oppression from within the narrative of modernity. TRI’s renderings of the former seem to be stripped of the latter, which makes the language used about the black women complicit in a fraught gaze at the Caribbean.

Mindful of its Biblical position, if we focus on the Greek for the term apocalypse, we do not necessarily come upon an insistent phallicism.(3) The prefix apo is read as un, and the root kaluptein is to cover. Unveilings, uncoverings that render alternative articulations of knowledge and desire proliferate throughout the region: the histories of hundreds of slave insurrections; self-sufficient maroon settlements in Brazil, the Guianas, Ecuador, Jamaica, and Cuba; the insistence that in vernacular, embodied, and lettered forms of expression, there was an ever-forming literature in the Caribbean despite the structure of the Plantation (Glissant); re-appropriations of the notion of Revolution, one which Europe’s bourgeoisie never had a proper hold on, but imported from decolonizing struggles throughout the Americas, Africa, and Asia (Lionnet and Shih); neocolonial struggles for cultural and ecological sustainability, and territorial sovereignty that coincides with a viable relation to the global economy.

What we read in the passages above is a contradiction regarding how to imagine the self, the nation, and the (available) historical processes of uncovering and overturning oppressive orders towards some sustainable liberation – one that is not romantic – in the Caribbean Americas. Román de la Campa writes in Latin Americanism (1999) that TRI conjures the unnamed black females as figures of “indifference” who signify “a form of popular disdain toward the very source of apocalyptic power from which such dangers derive” (112). That source would be US-Soviet relations, and their respective roles in Cold War discourse on sovereignty, politics, and power. De la Campa reads the performativity of the image of the black women as a potential deployment of postcolonial mimicry (111-120).(4) But we should also note that the language edges on positioning the image of the black women’s bodies as a stock example of exotic mystery – voiceless and legible only as rhythm.

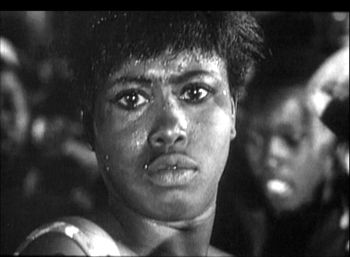

Benítez-Rojo’s notion of anti-apocalypse could be accurately re-figured through the voice of the character Pablo in Mds, Sergio’s friend who, notably, compares the Cuban Revolution to the Haitian Revolution as something bound to “regresar a la barbarie.” Such things as revolution belong “entre los rusos y los americanos,” not small islands, like Cuba (0.15.48-0.16.24). The rhetorical positioning of the old black women in TRI may also be reread through the opening credits of Mds and the presentation of a young black woman dancing. Drumming launches the film, and the hands of Pello El Afrokán carry the viewer through a large crowd into a close-up wherein one’s gaze is locked-into hers – she freezes us as the editorial hand has frozen her (0.02.04). This dance scene will reappear later in the film, but with Brouwer’s delicate score taking the  place of the diegetic drumming, and with Sergio amidst the crowd in which a man is shot, killed, and then carried away (1.14.13). The music goes on, but not for everyone in the crowd. We see the force of “carnivalesque catharsis” in this scene – of flesh, carne held within the word carnival, on rhythmic display, and as the corpse is carried out of the crowd, on ominous display. But the scene does not sublimate violence, nor outdo uncertainty; it inaugurates the film with both, and with an instrument that was played on the Plantation to summon the gods as well as revolt.

place of the diegetic drumming, and with Sergio amidst the crowd in which a man is shot, killed, and then carried away (1.14.13). The music goes on, but not for everyone in the crowd. We see the force of “carnivalesque catharsis” in this scene – of flesh, carne held within the word carnival, on rhythmic display, and as the corpse is carried out of the crowd, on ominous display. But the scene does not sublimate violence, nor outdo uncertainty; it inaugurates the film with both, and with an instrument that was played on the Plantation to summon the gods as well as revolt.

As TRI’s introduction points out, and the arguments of the “coloniality of power” critics and philosophers show in detail, the grossly elaborate “Plantation machinery” yielded the accumulation to upstart capitalism, and stretched from port to port throughout the New World, through the Middle Passage, into the pockets of Western Europe. But if the Plantation repeats as the very source of the rhythms, desires to self-differentiate, and performances prolific in Caribbean cultural life, then we cannot say that its enmeshed colonial violences are entirely sublimated. For this would require the kind of perilous forgetting that Walter Benjamin thoughtfully militates against in the Theses on the Philosophy of History (1950). If there is no assimilation in processes of mestizaje, which TRI’s introduction boldly writes off, since there were no fixed points of identity to begin with, but more traces of complexity, then violence, itself not fixed, cannot be blurred somehow into the landscape, the music, the excesses of language.

I posit the contrary: insurrections and the temptation of apocalypse may not be an origin in the Caribbean, but they are defining entanglements that delimit history’s reducibility to a sequence of transactions between the civilized suits of barbarity and the others. That is, for example, as Cuban Cinema of the 1970s showed (Lucía, Maluala, La última cena) when Western historiography, philosophy, and literary history still could not quite situate it, we may invoke the following event as partly constitutive of Caribbean-American desires for territorial sovereignty: a Revolution, a thirteen-year war of slaves against colonizers and the Plantation system in Haiti. This Revolution was placed under erasure for some three hundred years by Enlightenment philosophy, liberal-democratic and development politics (Buck-Morss; Fischer; Trouillot), though it was also contradictorily bound within those discourses. And the US, for its own reasons, has consistently mimed this attempt at discursive erasure regarding the Cuban Revolution (it was always already false, forced, and doomed).

The temptation to apocalypse – “to make the continuum of history explode,” as Benjamin calls it in Thesis XV – accompanies the revolutionary, self-determining national project. Likewise, it accompanies the modernist poetic project. J. Michael Dash opens his essay, “Postcolonial Eccentricities: Francophone Caribbean Literature and the fin de siècle” (2003), by stating that, “The single most important issue that has been raised in francophone Caribbean literature at the end of the twentieth century is arguably the conceptualization of the Caribbean region as a site for romantic fantasies of liberation or more precisely of redemptive or revolutionary apocalypse…” (33-34). In the Francophone Caribbean, we read the Peléan volcanic and vertical cry of négritude in Aimé Césaire’s Cahier d’un retour a pays natal (1939), and Frantz Fanon’s self-exhausting cry for love in Peau noir, masques blancs (1952), which preceded his chosen transplantation to Algeria as it became intensely bent on overturning the French colonial order. A poignant example of the mind divided by the temptation of apocalypse and departmentalization is in Césaire’s short piece “Panorama,” from the journal Tropiques (1941): “This land is suffering from a repressed revolution. Our revolution has been stolen from us… Martiniquan dependency – willed, calculated, reasoned as much as sentimental – will be neither dis-grace nor sub-grace… And in the last resort the resolution will come from the blood of this land. And this blood has its tolerances and its intolerances, patiences and impatiences…its calms and its whirlwinds” (in Refusal of the Shadow 79-81). As we do at the end of the Cahier, we read the climactic figure of a whirlwind, but here it blows beside the stilled calculations of economic strategy. We read here another attempt at reckoning with contradictory desires for a place.

I must hasten to add that while it is in many instances legible thereby in 20th century Caribbean and Latin American letters, the temptation of apocalypse does not have to be ciphered through the romantic. We may read it as impatience with Historicism’s rendering of time and events, as the desire for liberation to coincide with national-territorial sovereignty and practicable market relations (ones intra- and inter-national). For the temptation of apocalypse is part of a broader revolutionary imaginary in the Americas, and persists in time.

2. ¿Patria y qué más? – The Present’s Variables

Dash’s “Postcolonial Eccentricities” essay is framed by a refutation of TRI’s dismissal of apocalypse in the Caribbean and an elaboration on contemporary eccentricities and contradictions that Caribbean peoples must think through today. He states explicitly in the essay’s opening that “Benítez-Rojo’s very use of an apocalyptic tone…while declaring apocalypse to be profoundly un-Caribbean, is evidence of how easy it is to become enmeshed in ideological prescriptiveness” (35). Many ideological prescriptions have long shown their expiration dates. And the available terms for “postcolonial” nations have only complicated themselves. Speaking to this complexity of terminology, Dash delves into a list of descriptions that challenge the seemingly insurmountable historical differences between the islands of the French Overseas Departments (FODs) and Haiti, as a state that emerged from Revolution.

The ground he lays out will give traction to consider Cuba in the present, inasmuch as it could be imagined that Cuba and the FODs are poles of the Caribbean writ large and its history of liberation struggles, decolonization, “development” processes, and metropolitan dependencies. Dash writes:

The French Overseas Departments and Haiti, once seen as polar opposites – the exploded volcano versus the unexploded volcano; independence and isolation versus dependence and overdevelopment – are now both similar and exemplary in the way they have been thrust onto the global stage. It seems ironic that Haiti, where one-sixth of the population depends on USAID for nutrition [this is higher since the 2010 earthquake], and the French Overseas Departments, which have the highest consumption of Yoplait yogurt in the hemisphere, should share a common fate. Both, however, are thrust into a situation where they must be what they were and what they are with no idea as to what they will be… The francophone Caribbean no longer has a clear choice (if it ever did) between nation and elsewhere, or Africa and France… The question is rather whether they will be European, regional, hemispheric and yet Franco-Caribbean all at the same time. How will the geographic nation of Haiti relate to the tenth Department – the million or so Haitians now living in North America who represent a new extraterritorial concept of nation? Will French survive in Haiti, or do we have the makings of a situation (not unknown in the Caribbean) where English and Creole will coexist in the future? These are the realities of a francophone Caribbean fully in the grip of post-colonial anxiety (which still contains elements of neo-colonial and anti-colonial) of which the French Caribbean arguably represents the cutting edge…” (41, 42).

This list of “eccentricities” emerges from the anxieties generated by global capitalism for what Édouard Glissant called “small countries.” Growing diasporas, deepening linguistic crises given the expansion of global English, and varying forms of economic dependency intensify the question of traditional patrimony’s place. They lead us to wonder about the aesthetics to emerge and complicate this one among other questions of national-cultural identity and its points of articulation. And yet what is tricky, but must also be said, is that while there are legible similarities between Haiti and the FODs today, they cannot overshadow the cultural and political value – dare we call it a form of capital – that the histories of revolution and territorial sovereignty continue to offer.

As Dash instructs, the Francophone Caribbean represents a cutting edge of contradictions, but the Hispanophone Caribbean has been historically capable of brandishing a knife, and existing through just as many duplicities and questions as the ones we read above. This packed juxtaposition of Haiti and the FODs can be re-imagined between Cuba, The Dominican Republic, and Puerto Rico, given certain increasing economic similarities surrounding the (beach, sex, sun) tourist industry, and the cultural and linguistic concerns that grow from this situation.(5) Though we can also acknowledge that each island’s situation in the narrative of nationalism signifies differently. Beyond alluding to them, such juxtapositions exceed this essay’s scope. Here, Dash’s terms inspire a narrowing of thought with regards to Cuba’s relationship to itself: its history as a slave colony, as a Republic that rehearsed the ingrained racisms of its previous form, as a revolutionary society with a socialist state that shelved the discourse of race within that of class, one in the thick of ongoing negotiations about how to render this past in the present, how to sustain the Revolution’s narrative of difference today, and how to situate itself economically.

To riff on Dash’s language above for our purposes here: Cuba must imagine how to be what it was, what it is, and with great uncertainty about what it will be. To be what it was, is, with uncertainty of what will be requires juggling the contradictions of desire bound to the post-, neo-, and anti-colonial, which are not mere names, but different temporalities with accompanying economic and cultural variables that are simultaneously lived on the island. There is great uncertainty about a relation to the US, the hemisphere, and to Cuba’s diasporans, those “extraterritorial” nationals who return, or live here and there, physically constitute channels to the global economy, and carry other temporalities with them. The Franco-sketch above speaks to the challenges of thinking Cuba today, given its “postcolonial anxieties” and the present’s variables of time, diaspora, culture, and the economy that the signifier Revolution does not eclipse, but with which it cohabits.

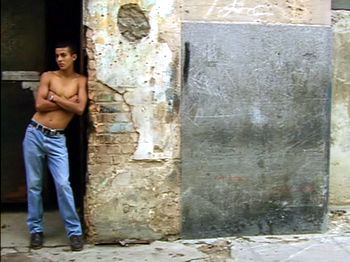

Because this essay deploys the metonymic mode of reading the nation as a peculiar and changing assemblage of parts, we must see that Dash’s passage above is a collection of metonyms in its own right (perhaps these sorts of collections become unavoidable when speaking Antillean). With its combination of the importance of apocalyptic events and postcolonial anxieties on our minds, we return to the image of the bicycle tire in the film, Mds, a metonym for movement being carried across a metonym for nationalism, muerte, which has marked the first half of how I want to frame the reader’s sight in this piece. We must ask of the letters beneath the paint: ¿Patria y qué más? Homeland and what other than death? While the  most visceral and phantasmal verse from the Cuban national anthem, “La Bayamesa,” rings in our ears – morir por la patria es vivir – one may desire an alternative relation to and love of place, one neither suicidal nor martyring, but nevertheless radical.(6) To install the other half of the frame of this essay: midway through Pérez’s cinematic homage to the Cuban capital, Suite Habana (SH, 2003), we see a brief scene that evokes the aforementioned one, in which the camera traces a different text of painted scrawl on a wall at a street corner. On one side of the wall leans a young mulatto man with arms crossed (30.56). The camera catches passers-by, a black man alone and then a group of several partly visible people, or they catch it, and lead viewers to what pins the other

most visceral and phantasmal verse from the Cuban national anthem, “La Bayamesa,” rings in our ears – morir por la patria es vivir – one may desire an alternative relation to and love of place, one neither suicidal nor martyring, but nevertheless radical.(6) To install the other half of the frame of this essay: midway through Pérez’s cinematic homage to the Cuban capital, Suite Habana (SH, 2003), we see a brief scene that evokes the aforementioned one, in which the camera traces a different text of painted scrawl on a wall at a street corner. On one side of the wall leans a young mulatto man with arms crossed (30.56). The camera catches passers-by, a black man alone and then a group of several partly visible people, or they catch it, and lead viewers to what pins the other  side of the frame: a bicycle resting against the wall beneath the verse painted thereon: “El rincón de la pasiencia” [sic] (31.04). This translates, Patience’s Corner, or, The Corner of Patience. Though one may, if punning, read it as The Edge of Patience. At this image’s edge, and between two films that touch the earliest and more recent moments in the Revolution’s narrative life, the metonymic tire has pulled itself into an assembled object, a bicycle poised for mounting, moving.

side of the frame: a bicycle resting against the wall beneath the verse painted thereon: “El rincón de la pasiencia” [sic] (31.04). This translates, Patience’s Corner, or, The Corner of Patience. Though one may, if punning, read it as The Edge of Patience. At this image’s edge, and between two films that touch the earliest and more recent moments in the Revolution’s narrative life, the metonymic tire has pulled itself into an assembled object, a bicycle poised for mounting, moving.

The transformation of this metonym, the bicycle tire now in a place, not standing in for but as part of an operative object – itself a metonym for a more complex desire for movement – situated beneath a visual insistence on patience, brings us to a tension: on the other side of the intense dictum, ¡Patria o muerte!, and amidst and after El período especial en tiempos de paz, both on and off the island a general thought has been that Cuba stood still, and that even now it is in a lingering malaise of stasis. Considering the many contradictory balls – economic, ideological, racial – suspended in the air of the 90s after a time in which hope and resistance had found traction, in which an alternate mode of socio-economic and national-cultural existence formed and were inhabited, one asks today: How long can this notion of suspense really last? How does one measure the movements of a place, a people? How many and what types of movements must be produced for them to be perceived as valuable? How do we imagine Cuba’s simultaneous need for what I call radical patience and “re-globalization” (Allen)?

Through readings of the films Fresa y chocolate (Fyc, 1993) and SH, the remainder of this essay engages some of these pressing questions. Fyc is positioned as a hinge between Mds and SH because of the two historical moments that it signifies: the late 70s, specifically 1979, in which it is set, and the early 90s, in which it is shot and released. It is through this film that I will elaborate the metonymic reading mode installed in Mds, which is the definitive organizing figure of SH, by discussing the operation of the cinematic cut. By looking at what is not altogether cut from the Revolution’s or Fyc’s narratives, we will see how the cinematic cut works hand-in-hand with a metonymic reading of Cuba’s national parts. This will lead into my discussion of SH, which shows that today, when the invocation of Homeland or death! may not seem audible, or even relevant, patience and micro-movements retrace on a small-scale the importance of apocalyptic entanglements in Caribbean, Cuban, American life.

3. The Cut in Fresa y chocolate

Though the conflict of how to imagine the constituents of the nation is global – as the notion of a “people” continues to be challenged, if not in some situations replaced by the term “multitude” (Hardt and Negri; Virno); by the idea that what nationalism eventuates is disagreement and displacement, not unification and a dream (Rancière) – here we are going to open some of Cuba’s specific discursive baggage in this conflict. By doing so, we will put into practice the metonymic reading mode that Mds and SH distinctly deploy.

To imagine the Cuban nation in the present, one must acknowledge the state’s ongoing yet changing crises with time and the global economy. These are related, inasmuch as Cuba is currently the only nation-state on the planet thriving on fifty plus years of socialist time, which, as we know, has (over)determined its relation to a late capitalist global economy. While one tendency north of the Florida Straits is to allude to Cuba’s socialism as a lingering condition, like a cough that won’t go away, the more relevant and desirous question is, how to rejuvenate this temporality and politics within an adjustment to global capital that benefits the nation? This is the quiet coda of SH. But before we look at its representational slices of Cuba’s national constituents, we must look at a member who was not successfully cut out of the picture, even though s/he appears as but a trace still in SH.

To understand the technical importance of a metonymic reading mode to this discussion of Cuban films, we must note how cinematic form distinctly leads the attentive eye to the joints, the places of movement – even if they are micro-movements – in life. A film, after all, cannot be made without objects in motion. Cinema is premised on turning space into time, as Arsenio Cué and Silvestre discuss in the novel Tres tristes tigres(1967) while driving along the Malecón. And yet, as the philosopher Alain Badiou words it, “A film operates through what it withdraws from the visible. The image is first cut from the visible. Movement is held up, inverted, arrested” (Badiou 78). Rather than rehearse the hackneyed Platonic notion wherein “the representation” of objects in the world is inferior to, if not a falsification of, those “real” objects, wherein language is situated with less than kinship and more of a handicapped dependency on the world, here we’ll imagine that cinematic form renders an irrefutable rupture between that which the camera faces and what that becomes, just as it thinks itself within that rupture. It assertively re-worlds objects and bodies, and it does so by making a cut, and then re-framing their visibility in an alternate world, which helps us imagine better ways of existing in this one.

In the essays that came to comprise What is Cinema? (1967), André Bazin shows that constitutive of cinema is its capacity to contain by re-presenting, re-thinking the other six arts. This only reinforces cinema’s power when compared with the other arts: its power is the cut. The cinematic transformation of a sequence of frames in relation to a notion of narrative or an expression of thought or a question of experience creates a distinct sense of transport for the human body, which is otherwise bound by its alienating task – to produce objects that can be turned either into use or exchange value – and strange relation to time – which today exists, as Gilles Deleuze instructs, for itself.

A jarring cinematic instance of the cut – an arrest of movement reconverted into another type of movement – occurs in Fyc just after the character Germán (the sculptor friend of the “Lezama-like” Diego) crashes himself into one of his sculpted saints, leaving it in pieces on the floor. Form is left in total conflict with content; the artist is conflated utterly with the object of his work; and the viewer is placed at a narrative impasse: what to do with this mess? As dust rises into the air from one of the ceramic bodies that resemble some coincidence of Jesus Christ and Karl Marx (Shaw 26), sticks to the artist’s hands, Germán continues the thrashing and crying over the remains: “¡Son mías, son mías, son mías…!” (1.00.09-1.01.04). While Diego’s becoming friends with David drives the film’s story about the relation between artist-thinker, homosexuality, and the revolutionary Cuban state, the figure of Germán and his vexed relationship to his art should not slip from sight. For it is the argument over exhibiting some rather than all of the sculptures that crowd Diego’s apartment that leads to his writing a letter to cultural functionaries that ends in his (off-screen) forced exile.

I want to emphasize the visual importance of the young homosexual artist’s self-destruction amidst aesthetic assertion, and how his being cut from narrative visibility thereafter only underscores the failed discursive erasure of homosexuals from Cuban social life. It is by deploying a metonymic reading practice that we can re-assert aspects of Germán’s figure. In the collision scene, Germán simultaneously breaks the face of one of his sculptures with his bare hands while declaring its possession as his alone. As he is bent over the object and the two appear as physical rivals, one realizes just how large the sculptures are. The artist’s collision with the near life-size figure suspends him between negative nihilism and metamorphosis, just as the question of historic accountability and the potential of having a place in the Revolution’s future also suspends Diego, whose collision, as a writer, is with the linguistic-imaginary rendering of Cuban national culture.

In Tropics of Desire: Interventions from Queer Latino America(2000), José Quiroga compares Diego to “Walter Benjamin’s angel of history, looking back and forward at a ruin, taking us back to other moments of crisis where the homosexual appears and disappears from the Cuban scene” (131). He continues: “All discussion about the film ends in a political cul-de-sac where visibility collides with desire. In other words, this might not be the film we want, but it is the film we have, and that is enough” (133). There is important cynicism laced into that last clause. But I am momentarily picking up on the collision of visibility and desire to which Quiroga alludes through the figure of Germán, who becomes part of the historical wreckage, and the negotiation of what to see and how – or, what to cut and how to portray the cut – that is important to the film’s, and to the Revolution’s, narrative.

The question of how History will record the homophobia and anti-poetics of the 60s and 70s in Cuba precedes the animation of this historical crisis in Germán’s figure. We recall that Fyc is a delayed cinematic rejoinder to Néstor Almendros’ and Orlando Jiménez Leal’s propagandistic documentary Conducta impropia (1984), whose footage of the violence against the heterogeneous departing body of queer, black, poor, and intellectuals amidst what became the Mariel Boat Lift is no less heartbreaking to watch. As a response, Fyc overcompensates by turning Diego’s character into a human teddy bear – non-threatening, for the most part contained by domestic space, and preferring nationalism to sex. Germán, on the contrary, articulates and signifies both sexual and aesthetic desires. His figure could have become the “homosexual cynic” who Quiroga notes is dangerously absent from the film (Tropics133) – and that he, in a sense, becomes as a rigorously critical yet meaningfully sentimental reader of the film. Instead, Germán is reduced to a set of gestos. But by practicing a metonymic reading, we can see in the lineaments of his figure’s collision with desire – specifically to exchange art on an international market – a re-assertion of it as a national part, and so, of Cuba as a possible common space shared by meaningfully fragmented desires.

Despite Fyc’s softening of the rough edges of representation, the artist’s collision with his creation retraces the figure of apocalypse. Like Diego’s reclamation of Cuba and his place in it, Germán’s reclamation of his creations comes amidst a self-collapse: these two scale down a portrayal of the mass violence of the 20th century Western State in the one space of refuge that remains for them, the demimonde of Diego’s apartment, where David, in turn, re-learns how to see Havana, the Revolution, and female form in his lessons from his mentor, and from the (banal) seduction of Nancy. Today, the apartment that served as the guarida of Diego in the film, where Quiroga brilliantly notes that “[c]ulture…sodomizes class,” has been turned into a somewhat over-priced state-sanctioned paladar attractive to tourists in-the-know and bands of study-abroad students (132).(7) Not only tourists, but also the state now consumes the remainders from the cultural “sodomizing” of class; this lightly tossed salad is plated and sold, and the figural yet again imbues the real with value.

Alas, in the film we are left looking through David’s heterosexual male gaze as he defends his relationship with Diego to the handsome and smug Miguel, as he pans the capital’s architectural gems amidst rubble and ruin, and, in the end, stands with Diego, who is headed into the body of the diaspora, and embraces him by the bay, that deep reminder of alternative market possibilities: fresa y chocolate, not fresa o chocolate. The melodramatic feeling struck by this final embrace retraces the violent attempt at Germán’s elision. To have to see through David’s eyes only intensifies the narrative violence done to the figure of the homosexual artist’s body. To not resist or agitate against having been forced to see this way becomes a form of complicity with the visual violence.

As we move into discussion of SH, I want the reader to continue seeing the violent embrace of Germán and his shattered sculpture, from which the feel-good prospect of reconciliation is absent.(8) As he gazes down onto the destruction of his hands over his creation, the face that has become a hole, he covers his own face with powdered hands and weeps wordlessly. There is no sublimation possible for this apocalypse and its wreckage. While reminding us of the general cinematic power of the cut, the removal of Germán from narrative visibility intensifies the questioning of sexually, racially, and ideologically non-normative presences in the Revolution in the 90s. For outside the window of Diego’s guarida in 1993, when Fyc was released, thousands of Cubans were preparing to depart and become balseros. As we re-assert their presences through a metonymic gaze, one of Cuba’s contemporary anxieties surfaces: how to navigate the categorical difference between exile and diaspora? While this question was already being asked in the late-90s, and continued being debated when SH was released in 2003, the matter still chafes today, even as it becomes only more vital to conceptions of the Cuban national future.

Fyc was released, thousands of Cubans were preparing to depart and become balseros. As we re-assert their presences through a metonymic gaze, one of Cuba’s contemporary anxieties surfaces: how to navigate the categorical difference between exile and diaspora? While this question was already being asked in the late-90s, and continued being debated when SH was released in 2003, the matter still chafes today, even as it becomes only more vital to conceptions of the Cuban national future.

On broad historical terms, after testimonies have been staged, written down, even filmed at times, after expressions of shame, apology, and the unforgiveable (that nevertheless seeks pardon) state violences have been articulated for legal and public record, the usual course of things is for the animate spaces of everyday life to differently renew, by transforming, their neglect. That is, for the crisis of vision that prompted such processes to be, as Germán easily could be, forgotten by the proverbial bigger story. Indeed, Fycis not enough, but its incapacity to sublimate apocalypse in a narrative of revolution, “gayness,” and diaspora brings us to a film that presents a plurality of national presences through an intimate and unique deployment of montage and the cut. It does not altogether dissolve ideological interpellation, but it artfully outwits the narrative ills from which Fyc suffers.

4. Bodies in Quotidian Motion: The Cut and Metonymy in Suite Habana

What now, when the notion of the bigger story has become a set of riddling variables produced by the tangle of nationalism and global markets? In the midst of the 90s’ tragedies, Ana López wrote that “the economic and social crises of ‘the special period’ have permanently invalidated the Revolutionary Utopian promise and have unmoored the fictions of insular national identity that once sustained the Revolution ideologically” (6). Insularity indeed aside, for its utopic fictions (which, as we just saw, relied on deep cuts) are not available to Cuban discourse today, we can carry this position across the time that has passed with some nuance. In ¡Venceremos?: The Erotics of Black Self-Making in Cuba (2011), an ethnographic and queer cultural study of Cuban black, homosexual, and variously self-named and state-labeled sex/erotic workers, Jafari Allen asserts:

Most Cubans are loyal to the revolutionary project, which liberated the majority from deplorable material conditions and provided the promise of a new society to which they could contribute and benefit. At the same time, this loyalty is constantly tested. Cubans suffer the effects of both global political-economic shifts and local mismanagement… They also suffer the effects of el bloqueo… (189).

While I resist categories such as “most” because there is no reliable corresponding measure for that adjective, in this important intervention we read a trace of the juggling act that Dash described pages back about how the Antilles must simultaneously be what they were, are, and with uncertainty about what will be. But uncertainty need not be conflated with indifference or straightforward ideology. The old binary of US capitalist/Cuba socialist is not sufficient to the complexities of the present. “[G]lobal capital, set in motion and protected by the United States state apparatus, [which] has as its imperative the consumption of every meter of the earth” enters the dynamic, and diverts the possibility any longer “that class is the primary axis of power that subsumes others, like race and gender and sexuality” (Allen190).

Ten years and several ICAIC films after Fyc, Pérez’s SH frames these concerns on a new scale. It turns the camera outside, transforms the re-education of David’s gaze at the city, and argues for belonging through everyday forms of communal participation. It offers a complex weave of images that accentuate the rituals of affect, tenderness, and sharing between bodies in the most minor and quotidian exchanges of life (Podalsky). I take issue with uncritical readings of the film as only a “celebration,” just as I do those that render it a “lament.” This film’s extraordinary capacity to use the cut to then weave images, to edit and thereby create a braid of connections between people as they move about their daily lives, and to use the cut metaphorically and beyond the visual in the realm of sound, by turning down the volume on dialogue to raise it on other types of sounds and voices, presents a film about duality and contradiction as part of the fabric of lived experience on an island that is today also nationally defined by its diaspora. As we see in the film, the present-absence of the diaspora is for the nation a tender if frustrated one, but this does not correspond to a narrative of disregard, nor, as one sees in the images of Mariel in 1980, violence towards the departing. Made in the midst of debates throughout

Ten years and several ICAIC films after Fyc, Pérez’s SH frames these concerns on a new scale. It turns the camera outside, transforms the re-education of David’s gaze at the city, and argues for belonging through everyday forms of communal participation. It offers a complex weave of images that accentuate the rituals of affect, tenderness, and sharing between bodies in the most minor and quotidian exchanges of life (Podalsky). I take issue with uncritical readings of the film as only a “celebration,” just as I do those that render it a “lament.” This film’s extraordinary capacity to use the cut to then weave images, to edit and thereby create a braid of connections between people as they move about their daily lives, and to use the cut metaphorically and beyond the visual in the realm of sound, by turning down the volume on dialogue to raise it on other types of sounds and voices, presents a film about duality and contradiction as part of the fabric of lived experience on an island that is today also nationally defined by its diaspora. As we see in the film, the present-absence of the diaspora is for the nation a tender if frustrated one, but this does not correspond to a narrative of disregard, nor, as one sees in the images of Mariel in 1980, violence towards the departing. Made in the midst of debates throughout the late 90s and early 2000s about a not strictly territorial but political, diasporic, and multiethnic cultural nationalism, SH relays these thoughts to viewers through visual and aural montage.(9) The cutting, weaving, and relaying of contradictions must be accounted for if one wishes to claim any critical relationship to this film as a work of art, and not merely a buttress to one ideology or another – which art, if it is worth its salt, resists. SH’s montage interrupts the narrative of national history rocking along a gradual, linear course. Extending the cinematic imprint of Gutiérrez Alea by drawing attention to itself, to cinematic language as capable of critiquing the notion of committed art, it meanwhile asserts the distinct signature of Pérez: an intimate, touching focus on the individual who is a crucial part of a complex, radical national community. Herein is an aesthetic response to the question, Homelandand what other than death?

the late 90s and early 2000s about a not strictly territorial but political, diasporic, and multiethnic cultural nationalism, SH relays these thoughts to viewers through visual and aural montage.(9) The cutting, weaving, and relaying of contradictions must be accounted for if one wishes to claim any critical relationship to this film as a work of art, and not merely a buttress to one ideology or another – which art, if it is worth its salt, resists. SH’s montage interrupts the narrative of national history rocking along a gradual, linear course. Extending the cinematic imprint of Gutiérrez Alea by drawing attention to itself, to cinematic language as capable of critiquing the notion of committed art, it meanwhile asserts the distinct signature of Pérez: an intimate, touching focus on the individual who is a crucial part of a complex, radical national community. Herein is an aesthetic response to the question, Homelandand what other than death?

In the course of one day and one night, this film shows figures in constant motion: riding bicycles, washing clothes, ironing, sorting the rations of food, attending school, dancing (in the ballet, at a timba concert packed with bodies and epistrophic thrusting, and in drag for tourists), repairing part of a house, leaving the island to join a Cuban lover in the diaspora, peddling to a second job after saying goodbye to the brother who has left the island. Formally, SH conjures fiction (Espina) in certain stagings of its subjects and scenes, the symphonic homage to a city (García Borrero), and mixes a “poetic” documentary mode, in its emphasis on fragmentary visual and aural repetitions, with an “observational” documentary mode by engaging the everyday lives of subjects often without seeming to interfere in them (Nichols).(10) In it, movement (kinesis, from which cinema derives), praxis, and everyday poiesis continue amidst uncertainty through quotidian micro-movements.

While everyday forms of repetition may seem a weak juxtaposition to grand historical arcs and flows, they offer a mode of thinking (with) the otherwise fragmented remainders of national parts piece-by-piece. To recall TRI’s emphasis on repetition as inherent to Caribbean aesthetic forms, the repetitions of everyday rituals made visible by SH argue that they are intimately constitutive of Cuban life. Here, too, these repetitions do not sublimate violence, but render a form of radical patience with the histories and inevitabilities of such ruptures on a small scale. But, I must add, repetition and the emphasis on metonymy in the film do not proverbially put Humpty Dumpty back together again. The film is not an argument for wholeness, and that particular Cartesian brand on the self, place, and existence has no applicability in the Caribbean. Repetition, metonymy, and the cut emphasize the breaks in the social fabric, lines that connect (phone lines) and disconnect (flight paths), and inscribe various ways of belonging to a place.

Pérez is one of the most praised Cuban directors since Gutiérrez Alea, winning numerous awards for Madagascar (1994), La vida es silbar (1999), and his most recent film, José Martí: El ojo del canario (2010), and is seen, by some, as thecineaste of the Special Period. But SH’s singular optic-sonic world is of keen interest here: while it is a film of no sustained audible dialogue, there is, nevertheless, language. Conversations take place before your eyes, interpellations are yelled, or puckered and sent through a kiss. Notably, of the nine distinct voices that are made audible in the film, six are female voices: an elementary school teacher’s (0.07.04-0.07.42); a female radio show host’s (0.12.06-0.12.27); a female  citizen crying out, “Giovanni,” presumably towards a child from her balcony (0.12.28; 0.13.55); the card reader of one of the principal subjects, Raquel (0.22.35-0.23.20); Bamboleo’s song, “Ya no hace falta,” sung with filmic emphasis on the verse, “déjame vivir en paz,” through the lips of the cross-dressing Iván – who stages the existence of otherwise unpresented queer bodies (1.07.37-1.08.52); and Omara Portuondo’s voice crying through “Quiéreme mucho” as the film closes (1.15.41-1.17.33) before its epilogue. Only some of the children counting with their maestra (0.07.04-0.07.42), Silvio Rodriguez singing “Mariposa” (57.50), and the announcer of the concert at El Salón Beny Moré (1.02.271.02.54) carry male timbres into the film. It is the re-worlded visibility of verbality that is emphasized by this volume control. The sounds of the city – some diegetic, others part of the studio-mixed “suite” – and the mechanics of basic life meanwhile over-determine the desire to relay dialogue in sound to the viewer.

citizen crying out, “Giovanni,” presumably towards a child from her balcony (0.12.28; 0.13.55); the card reader of one of the principal subjects, Raquel (0.22.35-0.23.20); Bamboleo’s song, “Ya no hace falta,” sung with filmic emphasis on the verse, “déjame vivir en paz,” through the lips of the cross-dressing Iván – who stages the existence of otherwise unpresented queer bodies (1.07.37-1.08.52); and Omara Portuondo’s voice crying through “Quiéreme mucho” as the film closes (1.15.41-1.17.33) before its epilogue. Only some of the children counting with their maestra (0.07.04-0.07.42), Silvio Rodriguez singing “Mariposa” (57.50), and the announcer of the concert at El Salón Beny Moré (1.02.271.02.54) carry male timbres into the film. It is the re-worlded visibility of verbality that is emphasized by this volume control. The sounds of the city – some diegetic, others part of the studio-mixed “suite” – and the mechanics of basic life meanwhile over-determine the desire to relay dialogue in sound to the viewer.

One does wonder: Is this because the spoken words of the film’s subjects do not matter? Or does this emphasis on the rituals of survival and the explicit shunning of muthos provoke the following reflection: that the state, the staid narrative of the Revolution, and notions of cultural and diasporic nationalisms are in flux, each lunging and intersecting to make sense of the riddles of economic interpellations today. In the film, not a silence (and yes, silence in Havana is imaginable to anyone who has walked its unlit streets at night) but a meticulous register of needs, concessions, foregone demands, delimited hopes, and thriving desires are portrayed as both active and actively ignored. These terms, feelings, and sounds exist alongside each other. Given the repetition of the microcosmic that delimits macro-speculative terms in this film, one must take care in approaching such breadth. And yet, while repeated minor images are key to the camera taking on an intimate presence in relation to its subjects, to facing what is effaceable, it is nevertheless impossible to say that macro-questions are forgotten. Instead, this emphasis on the micro- returns the mind to thought of the economy writ-large.(11) Knowing, however, that questioning it independent of the everyday goes nowhere – misses precisely the grounded details of existence that the film intensifies.

– misses precisely the grounded details of existence that the film intensifies.

Here, pistons pump in factory machines that coincide with the walk of the old manicerain colonial Havana, selling peanuts to get by (0.07.48-0.08.17); legs turn the pedals of a bicycle (0.2.23; 0.10.46; 0.25.25); arms tighten the giant bolts of the tracks of the railroad (0.20.42). This film is a collection of members, parts of a fragmented dream that come together in places, and break in others. Here, the visual renderings of the metonymic reading practice that we saw in Mds, which were themselves ways of referring back to the power and prerogative of the cinematic cut, have become a full-fledged mode of critique: braiding as well as breaking constitute a nation’s life. But added here to the apocalyptic, foreboding, and the uncertain is care – care for the self and a community.

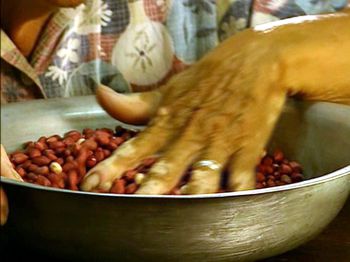

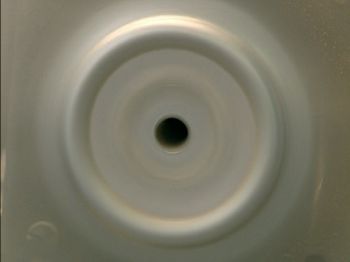

The poetic figure of the metonym is the explicit counterpart to SH’s usage of the cut. And there are at least five dominant and repeated visual-image metonyms of note: the tacones altos carried to and from repair by Iván on his bicycle (which he wears when he cross-dresses and performs for tourists, his female partner sitting among the largely male audience and anchoring for the viewer that his performance of transvestitism doesn’t leave the stage), which place him into relation with the elegant shoe- repairman, Julio; the hands of the manicera, Amanda, that reveal a skin pigmentation discoloration, and blend into the red-clay and cream colors of the peanuts that she carries in the familiar yet daily hand-crafted cone-shaped paper containers, and sells to some of the film’s other subjects; cracks and wrinkles: the viewer is repeatedly shown the oldest generation of Cubans in their 80s and 90s with not only middle-length shots but also extreme close-ups of wrinkles around eyes, hands, chests, which coincide with the cracks of architectural and infrastructural calamities; a repeated but obscure metal circle, which invokes Dziga Vertov’s “kino-glaz” (“cinema-eye”) – the lens of the camera that shows us images of the world that we would otherwise not see with our fallible human eyes – that is revealed as the center of the fan in the bedroom of

repairman, Julio; the hands of the manicera, Amanda, that reveal a skin pigmentation discoloration, and blend into the red-clay and cream colors of the peanuts that she carries in the familiar yet daily hand-crafted cone-shaped paper containers, and sells to some of the film’s other subjects; cracks and wrinkles: the viewer is repeatedly shown the oldest generation of Cubans in their 80s and 90s with not only middle-length shots but also extreme close-ups of wrinkles around eyes, hands, chests, which coincide with the cracks of architectural and infrastructural calamities; a repeated but obscure metal circle, which invokes Dziga Vertov’s “kino-glaz” (“cinema-eye”) – the lens of the camera that shows us images of the world that we would otherwise not see with our fallible human eyes – that is revealed as the center of the fan in the bedroom of the brother, Jorge Luis, entering the diaspora; and, lastly, the eye of the statue of John Lennon, which repeats the kino-glaz’s significance to this film precisely concerned with the everyday that when framed by cinematic thought becomes differently visible as an object for phenomenological questioning.(12) I say that there at least five dominant visual-image metonyms because smaller ones abound. But it could be argued that a sixth dominant one is the capital itself, Havana as metonymic of articulations of Cuba writ large. The differences portrayed among its inhabitants signify to us that there are still more differences between Havana and smaller cities and towns throughout the island were we to follow the oft-depicted train tracks outward.(13) [images 7-12 correspond to these metonyms]

the brother, Jorge Luis, entering the diaspora; and, lastly, the eye of the statue of John Lennon, which repeats the kino-glaz’s significance to this film precisely concerned with the everyday that when framed by cinematic thought becomes differently visible as an object for phenomenological questioning.(12) I say that there at least five dominant visual-image metonyms because smaller ones abound. But it could be argued that a sixth dominant one is the capital itself, Havana as metonymic of articulations of Cuba writ large. The differences portrayed among its inhabitants signify to us that there are still more differences between Havana and smaller cities and towns throughout the island were we to follow the oft-depicted train tracks outward.(13) [images 7-12 correspond to these metonyms]

As the film opens, before the sky dawns over the lighthouse, the bay, and the capital, we see the tongue of light in the lighthouse, a statue’s hand, then its face, that of John Lennon. First emphasized are parts that build into an ampler image of still more parts. We see the exchange of guards in El parque de John Lennon to protect the glasses of the statue (0.01.01). It was an apparently amusing prank to steal the thin metal frames off of the statue after it was installed in 2000, and as one of my student-artists pointed out upon seeing the film,  the welding of the frames looks fresh.(14) The response by the state was to mount an employee across from the statue to guard the glasses. Throughout the film, the camera plays on the false exchange of gazes between the guards and the dead eyes of the dreamer, Lennon. For while the state vigilantly protects that part – the sculpted frames – the guards sit in a lawn chair that has no back and a precarious bottom. After a period wherein houses were disassembled and turned into sea craft, prostitution became unabashedly endorsed by the state, and drugs, suddenly, entered the acknowledged litany of problems, this vigilant watch over a statue gestures to the ossification of certain dreams alongside the generation of others.

the welding of the frames looks fresh.(14) The response by the state was to mount an employee across from the statue to guard the glasses. Throughout the film, the camera plays on the false exchange of gazes between the guards and the dead eyes of the dreamer, Lennon. For while the state vigilantly protects that part – the sculpted frames – the guards sit in a lawn chair that has no back and a precarious bottom. After a period wherein houses were disassembled and turned into sea craft, prostitution became unabashedly endorsed by the state, and drugs, suddenly, entered the acknowledged litany of problems, this vigilant watch over a statue gestures to the ossification of certain dreams alongside the generation of others.

The repetition in SH of micro-movements and small parts intensifies the stakes of our metonymic mode of reading the nation, which has more value than one looking for homogeneity or grand connections. The rhetoric of renewed nationalism through monolithic resistance is not precise enough for the capacious contemporary contradictions of Cuban life. Quiroga shows in Cuban Palimpsests(2005)that there was no cohesive nationalistic theme available or imaginable for writers and artists of the 90s living with the scarcities depicted, for example, in Mirian Real’s recent documentary, Después de Paideia, o el rescate de una memoria(2011) about La Azotea of the poet, Reina María Rodríguez. In the images of the 90s, the attire of the Cuban population seemed to match the urban tilt, then bow, then collapse to gravity and neglect that left present actors, people, in an irreconcilable state of being that has many culpable parties.

Today, one walks along the Malecón and sees hundreds of svelte young men and women decked out in tight brand name clothes signify something outside the discourse of melancholy and scarcity. Consumption – and of brands that redundantly signify: black market and capitalism – is demonstrated assertively, at times aggressively, with a relation always to eroticism and a desire for agency that bobs-and-weaves in a match with a notion of the self that is nevertheless in the ring of global capital, which is, in part, a force hell-bent on the death. This shift from Cuba being a place of bodies open to tourist consumption after the mid-90s to one of bodies actively, if within definite limits, consuming and signifying the desire to do so marks an important shift after the roughly fifteen-year (if not informally longer) Special Period.

While there is not a conclusive way to read this shift, we can believe that cultural memory is not short. By inhabiting a radical patience with the present’s riddles and promises, we do not betray the political and cultural importance of apocalyptic histories and potentials of future ruptures, nor do we long for a romantic or nostalgic national form unavailable today. We can take stock in the words of the poet Jay Wright who, invoking José Martí, tells us: “The historical experience loses nothing. The landscape speaks… The people who endure in history…are the imaginative ones” (Wright 20). Patience in this time of uncertainty may generate the imaginary space to rejuvenate a politics not utopic, but heterotopic, an economy not exploited or exploitative, but viable.

5. Uncertainty and Endurance

There were riots in Havana’s streets in the early 90s, and a climax of such by 1994. An estimated 125,000 people took to open waters, to the possibility of oblivion or Miami, between 1990 and 1994. (Herein we have a nihilistic re-interpretation of Patria o muerte, and another manifestation of apocalyptic desire.) What became Wim Wenders’ The Buena Vista Social Club (2004) was being arranged (unaware of the future’s nostalgic musical appetite) by the hands of Juan de Marcos González after a detour from a musical collaboration between a few of the Cuban musicians that made Ry Cooder’s bill and several Malian musicians. The collaborative Catalan-Spanish-Cuban documentary Balseros (2002) was in the making. Writers and artists peopled La Azotea, and later La Torre de Letras. The characters of Z. and Linda of Cien botellas en una pared (2002), the performances of Tania Bruguera, Juan Carlos Flores, and Omni Zona Franca all offer images of making art from quotidian routines. As the conditions of these movements are heterotopic rather than utopic, they demand reading Cuba today through its metonyms, and their varied modes of resisting, living, and feeling.

After roughly fifteen years characterized by scarcity and uncertainty, the last few years have been marked by debates about the emergence and control of private markets alongside that of the state. The “cuenta propia” list produced by the state in 2010 for citizens offers a curious stamp on this discursive shift, itemizing possible private sector jobs, among them performing as a “dandy” in the lately refurbished Old Havana. Citizens become character actors, lost extras from the set of Humberto Solás’ Cecilia(1983). Today, it is as though there is a re-arrangement of what one heard from Castro and then saw on the wall in Mds. Not “¡Patria o muerte!” or Patria o muerte, but Patria and patience. The latter does not negate the historical importance of the former two, but more accurately speaks to the present.

state in 2010 for citizens offers a curious stamp on this discursive shift, itemizing possible private sector jobs, among them performing as a “dandy” in the lately refurbished Old Havana. Citizens become character actors, lost extras from the set of Humberto Solás’ Cecilia(1983). Today, it is as though there is a re-arrangement of what one heard from Castro and then saw on the wall in Mds. Not “¡Patria o muerte!” or Patria o muerte, but Patria and patience. The latter does not negate the historical importance of the former two, but more accurately speaks to the present.

As we see in the images of women’s work in SH – in the hands of Inés, Heriberto’s mother, carefully weaving buttons into place – patience may be turned into an imaginative tool that does not disregard the historical importance of apocalypse and liberatory desires, nor fall into the trap of passivity, nor that of self-exoticization without agency.(15) For a practiced radical patience retraces the whirlwinds held in Césaire’s Cahier. While the gusts of global capitalism are recently experiencing some crosses in current, that they howl destructively in the direction of the indefinite Antilles is irrefutable. Like the winds of “progress” that plunged Benjamin’s Angel forward, these can, in minor ways, be militated against with an eye re-educated by the metonymic gaze, a cynical vision that loves the fragments that constitute a place. [image 14]

Notes

1. See Josefina Saldaña-Portillo’s The Revolutionary Imagination in the Americas for a rigorous study of confluences between rhetorics of revolutionary nationalism and development.2. In the novel Memorias, Sergio has sex with Noemí, in the midst of which they hear the radio voice of President Kennedy auguring nuclear war.

3. This reference to “phallicism” on page ten of the English translation of La isla que se repite is not on the corresponding page xiii of the Spanish original.

4. De la Campa’s reading of Benítez-Rojo and Glissant has been re-worked in the recent essay, “El caribe y su apuesta teórica” published in SUR/Versión in 2011 (Caracas, Venezuela).

5. For more on the shift in the 90s and early 2000s into tourist and dollar-driven markets in Cuba, see Esther Whitfield’s Cuban Currency. The introduction critiques Néstor García Canclini’s notion of citizen-consumers as inapplicable to Cubans during the Special Period. This is a rich discussion, to which I would add that today we are seeing precisely this shift in Cuba towards a form of consumer-citizenship in a socialist state with more market possibilities.

6. My thanks to the reviewer who recalled the lyrics of the Cuban national anthem, La Bayamesa, as well as Louis Pérez Jr.’s thoughtful and painstaking study of the historical and unusually high rates of suicides in Cuba from the plantation period to the Special Period. Suicide as actuality and within rhetoric of national devotion renders an ominous rejoinder to Benítez-Rojo’s insistence on Caribbean sublimations of violence.

7. My thanks to Michael Gutierrez for word about Diego’s guarida as paladar.

8. In July, the theme of the prominent journal Temas’ último jueves debate was reconciliation. Patrimony’s relation to the Cuban diaspora continues to be a debated, yet unavoidable, part of Cuban experience.

9. See Ariana Hernandez-Reguant’s essay, “Multicubanidad,” in her Cuba in the Special Period collection, for a well-wrought narrative on the debates about cultural and diasporic nationalisms in the mid-90s and into recent years.

10. To articulate SH’s many cinematic references and techniques requires more exhaustive work. It is my hope that the limited job done here cues the reader to how the film thinks, how it re-worlds a set of movements and figures so as to reshape hope and resistance in this world. Tim Corrigan’s new book, The Essay Film: From Montaigne, After Marker, an exacting and fresh study, provides a succinct rendering of Deleuze’s notion in Cinema I and Cinema 2 of the thinking of cinema, or cinema as thinking, specifically in relation to the essay-film as a dialogic engagement of subjectivity and experience (33, 34). Among other reasons, for its presentation of a protean and changing/questioning individual subject, I am not prepared to argue that SH is an essay film. Yet, considering its processes of reflection in relation to those of the film as essay is fruitful. SH’s subjects exist in relation to a heroic public narrative of the Revolution, and this is not ever forgotten as a viewer. But, if we imagine the Revolution as the subject among all of SH’s individual subjects, then its presentation through everyday rituals of habitation in Havana, through visual and aural metonymy and montage rather than narrative, conveys something protean and re-shaping about it. Not to mix messages, but it is meaningful that Pérez has an essayistic attitude about the documentary, as articulated in his interview with Ann Marie Stock: “I’d like for spectators, after having watched the film, to ask themselves: What is the meaning of life? What type of life am I living? What dreams do I or don’t I have?...What type of life surrounds me? What is my context?” For Cuban spectators to ask these questions is to suggest mutability, so also viability, of the Revolution.

11. I have used the term market(s) in this essay alongside the term economy. In using both at different moments, I mean to suggest that smaller, localized markets demand imagination in our approaches to thinking alternate existences within the global economy. As we must be guarded about the glob in globalization, the reduction of world in mondialisation, we must imagine plurality within late capitalism’s “logic.”