On the Legitimacy of Darío’s “Las siete bastardas de Apolo”

Raymond Skyrme, University of Toronto

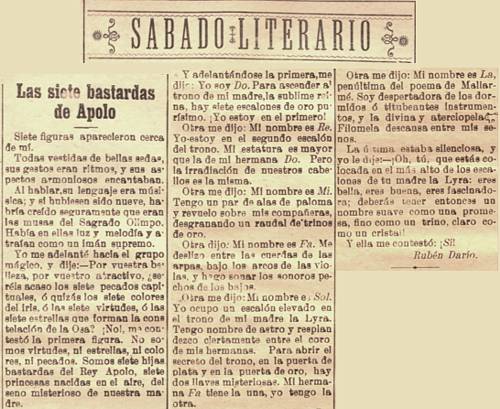

A recent study of Darío’s pitagorismo focuses long-overdue attention on “Las siete bastardas de Apolo” (Carlo-Torres, 102-29). In its light tone and allegorical setting the story provides a unique and unsuspected formulation of the central role of music as the creative principle in Dario’s vision of the universe. The version of the text analysed is that presented in Cuentos completos (ed. Julio Valle-Casrillo):

A recent study of Darío’s pitagorismo focuses long-overdue attention on “Las siete bastardas de Apolo” (Carlo-Torres, 102-29). In its light tone and allegorical setting the story provides a unique and unsuspected formulation of the central role of music as the creative principle in Dario’s vision of the universe. The version of the text analysed is that presented in Cuentos completos (ed. Julio Valle-Casrillo):

Las siete figuras aparecieron cerca de mí. Todas vestidas de bellas sedas; sus gestos eran ritmos, y sus aspectos armoniosos encantaban.

Al hablar, su lenguaje era musical; y si hubiesen sido nueve, habría creído seguramente que eran las musas del sagrado Olimpo. Había en ellas mucha luz y melodía, y atraían como un imán supremo.

Yo me adelanté hacia el grupo mágico, y dije:

--Por vuestra belleza, por vuestro atracivo, ¡estéis [sic] acaso los siete pecados capitales, o quizás los siete colores del iris, o las siete virtudes, o las siete estrellas que forman la constelación de la Ossa?

--¡No! --me contestó la primera--. No somos virtudes, ni estrellas, ni colores, ni pecados. Somos siete hijas bastardas del rey Apolo; siete princesas nacidas en el aire, del seno misterioso de nuestra madre la Lira.

Y adelantándose me dijo además:

--Yo soy DO. Para ascender al trono de mi madre la sublime Reina, hay siete escalones de oro purísimo. Yo estoy en el primero.

Otra me dijo:

--Mi nombre es RE. Yo estoy en el segundo escalón del trono. Mi estatura es mayor que la de mi hermana DO. Pero la irradiación de nuestros cabellos es la misma.

Otra me dijo:

--Mi nombre es MI. Tengo un par de alas de paloma, y revuelo sobre mis compañeros [sic], desgranando un raudal de oro.

Otra me dijo:

Mi nombre es FA. Me deslizo entre las cuerdas de las arpas, bajo los arcos de las violas. Y hago vibrar los sonoros pechos de los bajos.

Otra me dijo:

--Mi nombre es SOL. Yo ocupo un escalón elevado en el trono de mi madre la Lira. Tengo nombre de astro y resplandezco ciertamente entre el coro de mis hermanas. Para abrir el secreto del trono en la puerta de plata y en la puerta de oro, hay dos llaves misteriosas. Mi hermana FA tiene la una, yo tengo la otra.

Otra me dijo:

Mi nombre es LA. Penúltima del poema del Sonido. Soy despertadora de los dormidos y [sic] titubeantes instrumentos, y la divina y aterciopelada Filomela descansa entre mis senos.

La última estaba silenciosa; yo le dije:

--!Oh, tú, que estás colocada en el más alto de los escalones de tu madre la Lira. Eres bella, eres buena, fascinadora: deberás tener entonces un nombre suave como una promesa, fino como un trino, claro como un cristal.

Ella me contestó dulcemente:

--Sí. (367-68).

This text, including the three errors noted, is an exact replica of that established by Ernesto Mejía Sánchez in his Cuentos completos de Rubén Darío. Valle-Castillo also reprints the “Estudio preliminar” of Raimundo Lida. More importantly, this edition also reproduces Mejía Sánchez’s footnote to the story, which outlines the publishing history of the text from 1903 to 1950. The footnote reads:

El Cubano Libre, Santiago de Cuba, 1 de agosto de 1903 (cf. Saavedra Molina; Bibliografía, p. 85); de ahí lo recogió Regino E. Boti para El árbol del rey David, 1921, pp. 41-44. En los Primeros cuentos, Madrid, 1924, pp. 149-154, lo reproducen con alteraciones y erratas. Hemos preferido el texto de Boti (278).

The Primeros cuentos text which Mejía Sánchez rejects for its “alteraciones y erratas” is in Vol. 3 of Obras completas (Ed. Alberto Ghiraldo y Andrés González-Blanco). This text is reproduced in Vol. 4 of Obras completas. 5 vols (Afrodisio Aguado, 1955), 75-77.

The three differences between the Boti and Ghiraldo y González-Blanco texts are shown in the following table (line references are to the Valle-Castillo text quoted above):

| # | Line | Boti | Ghiraldo/González-Blanco |

| 1 | 3 | Su lenguaje era musical | Sus lenguajes eran música |

| 2 | 33 | LA. Penúltima del poema del Sonido | La, penúltima del poema de Mallarmé |

| 3 | 40 | Ella me contestó dulcemente | Y ella contestó sonriente |

Leaving aside for a moment Mejía Sánchez’s charge of “alteraciones y erratas” in the Ghiraldo y González-Blanco version, it may be helpful to compare each pair of differences within the context of Darío’s text, more of a poema en prosa, perhaps, than a cuento.

The difference between versions seems slightest in #3. But while “dulcemente,” echoing the classic formula of maidenly consent, dar el dulce sí, “sonriente” implies more. The last of the “siete figuras,” is the only one who does not identify herself, silently encouraging the speaker’s honeyed phrases before, with a smile, both coyly accepting his courtship and ironically playing on the double meaning of her “sí,” both “yes” and the alternate form of her name, TI.(1)

consent, dar el dulce sí, “sonriente” implies more. The last of the “siete figuras,” is the only one who does not identify herself, silently encouraging the speaker’s honeyed phrases before, with a smile, both coyly accepting his courtship and ironically playing on the double meaning of her “sí,” both “yes” and the alternate form of her name, TI.(1)

The difference between the sentences in #1 is not merely grammatical but stylistic and semantic. “Sus lenguajes eran música,” echoing the syntax and style of “Sus gestos eran ritmos” in line 2, is metaphorical, unlike the prosaically descriptive “Su lenguaje era musical”: their words are not merely like music, they are music, just as their gestures are rhythms. As the “bastardas” will later reveal in their own words, they are the embodiment of what Darío and others, including Mallarmé, saw as the universal creative force.

This factor alone should be enough to justify the reference to Mallarmé in #2. But a source elsewhere in Darío’s work explains why LA introduces herself as “Penúltima del poema de Mallarmé.” In his perceptive “estudio,” written for El Mercurio de América shortly after the French poet’s death in 1898, Darío names the “poema,” which is not a poem in verse but in prose, entitled “La Pénultième” (IV: 913-20), and now known as “Le démon de l’analogie.” But the relevance of “La Pénultième” goes beyond the title. LA’s definition of herself also echoes the theme of Mallarmé’s poème en prose, which one editor of the poet’s work has described as the “Naissance du Poème” (Pages choisies 78).

LA presents herself, in an image reminiscent of Bécquer’s “Rima VII,” as the midwife to poetic birth, “despertadora de los dormidos o titubeantes instrumentos.”(2) As the note (A) produced by the tuning fork it is LA who tunes up the orchestra, bringing to life what in “La tortuga de oro” Darío calls “lo que está suspenso entre el violín y el arco” (V: 1312). She has the power to generate the infinite number of melodies and harmonies suggested in the earlier remarks of the narrator and her sisters, FA and SOL. The same metaphor of not only poetic awakening but the unbreakable will to create informs the allusion to the myth of Philomela, weaving into a tapestry the atrocity of her rape by Tereus, who had sought to ensure her silence about the crime by cutting out her tongue (Ovid 143-51).

Malarmé’s poetic myth is typically hermetic compared with the fairy-tale directness of Darío’s fable:

Le démon de l’analogie

Des paroles inconnues chantèrent-elles sur vos lèvres, lambeaux maudits d'une phrase absurde?

Je sortis de mon appartement avec la sensation propre d'une aile glissant sur les cordes d'un instrument, traînante et légère, que remplaça une voix prononçant les mots sur un ton descendant: «La Pénultième est morte», de façon queLa Pénultième

finit le vers et

Est morte

se détacha de la suspension fatidique plus inutilement en le vide de signification. Je fis des pas dans la rue et reconnus en le son nul la corde tendue de l'instrument de musique, qui était oublié et que le glorieux Souvenir certainement venait de visiter de son aile ou d'une palme et, le doigt sur l'artifice du mystère, je souris et implorai de voeux intellectuels une spéculation différente. La phrase revint, virtuelle, dégagée d'une chute antérieure de plume ou de rameau, dorénavant à travers la voix entendue jusqu'à ce qu'enfin elle s'articula seule, vivant de sa personnalité. J'allais (ne me contentant plus d'une perception) la lisant en fin de vers, et, une fois, comme un essai, l'adaptant à mon parler; bientôt la prononçant avec un silence après «Pénultième» dans lequel je trouvais une pénible jouissance: «La Pénultième» puis la corde de l'instrument, si tendue en l'oubli sur le son nul, cassait sans doute, et j'ajoutais en manière d'oraison: «Est morte. » Je ne discontinuai pas de tenter un retour à des pensées de prédilection, alléguant, pour me calmer, que, certes, pénultième est le terme du lexique qui signifie l'avant-dernière syllabe des vocables, et son apparition, le reste mal abjuré d'un labeur de linguistique par lequel quotidiennement sanglote de s'interrompre ma noble faculté poétique: la sonorité même et l'air de mensonge assumé par la hâte de la facile affirmation étaient une cause de tourment. Harcelé, je résolus de laisser les mots de triste nature errer eux-mêmes sur ma bouche, et j'allai murmurant avec l'intonation susceptible de condoléance: «La Pénultième est morte, elle est morte, bien morte, la désespérée Pénultième», croyant par là satisfaire l'inquiétude, et non sans le secret espoir de l'ensevelir en l'amplification de la psalmodie quand, effroi!--d'une magie aisément déductible et nerveuse--je sentis que j'avais, ma main réfléchie par un vitrage de boutique y faisant le geste d'une caresse qui descend sur quelque chose, la voix même (la première, qui indubitablement avait été l'unique).

Mais où s'installe l'irrécusable intervention du surnaturel, et le commencement de l'angoisse sous laquelle agonise mon esprit naguère seigneur c'est quand je vis, levant les yeux, dans la rue des antiquaires instinctivement suivie, que j'étais devant la boutique d'un luthier vendeur de vieux instruments pendus au mur, et, à terre, des palmes jaunes et les ailes enfouies en l'ombre, d'oiseaux anciens. Je m'enfuis, bizarre, personne condamnée à porter probablement le deuil de l'inexplicable Pénultième (Oeuvres, 272-73).

The Demon of Analogy

Did unknown words sing upon your lips, the accursed rags of an absurd phrase?

I left my flat with the very feeling of a wing slipping over the strings of an instrument, light and lingering, and replaced by a voice which pronounced in a descending scale the words: “The Penultimate is dead,” in such a way that

The Penultimate

ended the line and

Is dead

stood out from the fateful phrase most uselessly in the absence of meaning. I took some steps in the street and recognized in the null sound the stretched cord of the musical instrument which had been forgotten and which glorious Memory had certainly just visited with its wing or with a palm and, my finger on the mystery’s contrivance, I smiled and implored a different subject of speculation with intellectual desires. The phrase recurred, virtual, detached from an earlier fall of feather or branch, henceforward heard through the voice until at last it was pronounced by itself, living with its own personality. I went along (no longer being satisfied with a perception) reading it like the end of a line of verse, and, once, as an experiment, adapting it to my speech; soon pronouncing it with a silence after “Penultimate” in which I found a painful pleasure: “The Penultimate”—then the instrument’s string, so stretched in forgetfulness over the null sound, broke doubtless, and I added as a sort of prayer: “Is dead.” I did not cease attempting a return to favourite thoughts, claiming, to calm myself, that, to be sure, penultimate is the dictionary term meaning the last syllable but one of words, and in appearance the ill-renounced remains of a linguistic task by which my noble poetic gift daily sobs to see itself interrupted: even the sonority and the air of falsehood assumed by the haste of the false affirmation were a cause of torture. Worried, I resolved to follow the words of melancholy kind to wander themselves on my lips, and I walked murmuring with an intonation capable of sympathy: “The Penultimate is dead, is dead, quite dead, the wretched Penultimate,” thinking that in this way I could satisfy my uneasiness, and not without the secret hope of burying it in the expansion of the chant when, horrors!—by an easily explicable, nervous magic—I felt that, while my hand reflected in a shop window made the gesture of a caress coming down on something, I possessed the voice itself (the first voice, which indubitably had been the only one).

But the moment at which there took place the irrefutable intervention of the supernatural and the beginning of the anguish beneath which my once lonely spirit agonizes, was when I saw, raising my eyes, in the street of antique dealers which I had followed instinctively, that I was in front of a lute-maker’s shop selling old musical instruments hung on the wall, and, on the ground, some yellow palms and the wings of old birds hidden in the shadow. Like an eccentric I fled, a person probably condemned to wear mourning for the inexplicable Penultimate (Mallarmé, 1965: 123-25).

Guy Delfel comments on the importance of “Le démon de l’analogie” as follows: “Mallarmé nous y laisse surprendre sur un example ses secrets de fabrication en même temps que la source de son hermétisme” (Pages choisies, 78). The components of Mallarmé’s poème en prose (ton, corde, glisser, archet, plume, aile, instrument), like their counterparts in Darío’s cuento (cuerda, me deslizo, arco, alas, viola, bajos, instrumentos), provide an invaluable insight into what is central to their view of poetry and the world: the creative, ordering principle of music. Mallarmé referred to it as “Idée ou rythme entre des rapports” (Oeuvres 647); Darío, as “el armonioso enigma que es ritmo de la esfera” (V 121).(3)

Guy Delfel comments on the importance of “Le démon de l’analogie” as follows: “Mallarmé nous y laisse surprendre sur un example ses secrets de fabrication en même temps que la source de son hermétisme” (Pages choisies, 78). The components of Mallarmé’s poème en prose (ton, corde, glisser, archet, plume, aile, instrument), like their counterparts in Darío’s cuento (cuerda, me deslizo, arco, alas, viola, bajos, instrumentos), provide an invaluable insight into what is central to their view of poetry and the world: the creative, ordering principle of music. Mallarmé referred to it as “Idée ou rythme entre des rapports” (Oeuvres 647); Darío, as “el armonioso enigma que es ritmo de la esfera” (V 121).(3)

Against all that the reference to the “poema de Mallarmé” ultimately implies, the phrase “poema del Sonido” in the Boti edition of Darío’s cuento seems feeble and above all static, merely descriptive of LA’s position on the escala musical of the Lira, incapable of evoking the dynamic process of poesis that Mallarmé’s poetic rêverie suggests.

Finally, the reference to a real figure in the real world outside that of the allegorical one which LA and her sisters inhabit, does not diminish its validity. Unlike the other, mythical figures invoked (Apollo, Lyra, Philomela) it indicates the seriousness of what Darío is saying about his poetic credo despite the apparent frivolousness of the fable’s title.

On the basis of the internal evidence of the text it would be hard to deny the validity of the 1924 version of Darío’s cuento despite the opinion of such a respected authority on Darío as Ernesto Mejía Sánchez. But Mejía Sánchez does not appear to have seen the original publication of 1903, relying on the information provided by Saavedra Molina, who makes no comment on the text, only on the date and place of its first

appearance.(4) In including the 1921 Boti version in his 1950 edition of Darío’s Cuentos completos, he assumes, it would appear, that Boti had faithfully reproduced the original text (“de ahí lo recogió Regino E. Boti,” 78). Only the evidence of what appeared in the August 1, 1903 issue of El cubano libre will determine whether Boti’s 1921 or Ghiraldo y González Blanco’s 1924 version is the legitimate one.

Gaining access to such evidence was not easy. But finally a scan of the August 1, 1903 issue was obtained from the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Darío’s cuento appears as a single column in the middle of the section devoted to literature. It contains one printing error in lines 6-7: “músi-sica.” A summary of the three passages in dispute is given in the following table. Line numbers refer to those of the El cubano libre text, reproduced above in two columns:

| # | Line |

Boti |

Ghiraldo/González -Blanco |

El cubano libre |

1 |

6-7 |

Su lenguaje |

Sus lenguajes |

Su lenguaje era |

2 |

57-59 |

LA. Penúltima del |

La, penúltima del |

La, penúltima del |

3 |

73 |

Ella me contestó |

Y ella contestó |

Y ella me contestó |

In item #3, earlier treated as the least important discrepancy between the 1921 and 1924 editions, both Boti and Ghiraldo y González-Blanco gild the lily, perhaps for reasons suggested earlier, adding “dulcemente” and “sonriente” respectively. Boti retains the singular “Su lenguaje era” in #1 but changes “músi-sica” to “musical.” Most importantly in #2 he replaces the powerfully evocative “poema de Mallarmé” with the weakly prosaic “poema del Sonido.”(5)

On balance, what might be considered the truly bastard version of Darío’s cuento, with its more serious “alteraciones,” was fathered by Boti in 1921, and protected henceforth by Mejía Sánchez and those editors who in 1990 and 2005(6) followed his authoritative example. On the other hand, despite the addition of “sonriente” in #3 and the change of singular to plural in #1, Ghiraldo y González- Blanco, and the 1955 Afrodisio Aguado edition of Darío’s Obras completas which followed them, come close to preserving the legitimacy of the original 1903 text. In doing so they safeguard what within his Pythagorean worldview is one of Darío’s most persuasive poetic utterances.(7)

Notes

1. Given her silence, perhaps Darío is embodying in the seventh sister, SI or TI, the added function of the musical rest.

2. ¡Cuánta nota dormía en sus cuerdas,

como el pájaro duerme en las ramas,

esperando la mano de nieve

que sabe arrancarlas! (Rimas 204)

3. For a detailed discussion of Darío, Mallarmé, and music, see Skyrme, 60-87.

4. Given Mejía Sánchez’s apparent lapse, Saavedra Molina’s candour in the “Advertencias” to his Bibliografía is ironic: “Es inútil […] que pida excusas por mis omisiones o errores, que a veces se deberán a la inexacta información recibida de otros. Por esto, he cuidado de advertir ‘No lo he visto,’ cada vez que mis datos no proceden de una inspección personal del libro o folleto mencionados” (8).

5. There is no defence for making such a change, even if Boti was not familiar with Mallarmé’s work or was not aware of Darío’s critique of it.

6. In this edition, Managua: Anama, 2005, Iván Uriarte has corrected the two errors introduced by Mejía Sánchez in 1950: “Estéis|” to “Seréis” and “compañeros” to “compañeras.” However, he leaves uncorrected (to “o”) the third error, “y,” introduced by Boti and adopted by Mejía Sánchez (259).

7. I wish to thank Adriana Sgro, University of Toronto Scarborough Library, for her expertise in locating the editions so essential to this study; and Wilfrid R. Morency for his indispensable help in the preparation of the manuscript.

Works Cited

Bécquer, Gustavo Adolfo. Rimas. Edición crítica de Russell P. Sebold. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, 1989.

Carlo-Torres, Senén E. Tendencias Filosóficas, Científicas y Esotéricas en la Obra de Cambaceres, Darío, Lugones. Diss. Temple University. 2008.

Darío, Rubén. Cuentos completos. Ed. Ernesto Mejía Sánchez. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1950.

--------. Cuentos completos. Ed. Julio Valle-Castillo. La Habana: Editorial Arte y Literatura, 1990.

--------. Cuentos completos. Ed. Iván Uriarte. Managua: Anama, 2005.

--------. El árbol del rey David. Ed. Regino E. Boti. La Habana: Imprenta “El Siglo XX,” 1921.

--------. “Las siete bastardas de Apolo.” El cubano libre, August 1. Santiago de Cuba, 1903.

--------. Obras completas. 5 vols. Madrid: Afrodisio Aguado, 1955.

--------. Primeros cuentos. Eds. Alberto Ghiraldo y Andrés González-Blanco.

--------. Obras completas. Vol 3. 17 vols. Madrid: Biblioteca Rubén Darío, 1924.

Mallarmé, Stéphane. Oeuvres complètes. Pais: Gallimard, 1945.

Mallarmé, Stéphane. Mallarmé. Introduced and edited by Anthony Hartley. Penguin Books Ltd, 1965.

--------. Pages choisies. Ed. Guy Delfel. Paris: Librairie Hachette, 1954.

Ovid. Metamorphoses. Trans. Rolfe Humphries. London: Heinemann, 1956.

Saavedra Molina, Julio. Bibliografía de Rubén Darío. Santiago de Chile: Revista Chilena de Historia y Geografía, 1945.

Skyrme, Raymond. Rubén Darío and the Pythagorean Tradition. University of Florida Press, 1975.