[Photograph of Pedro Marqués in Madrid: Kristin Dykstra, 2009.]

Notices on Obits

Kristin Dykstra, Illinois State University

In 2003, Italy’s International Writers’ Parliament invited Pedro Marqués to travel from Cuba to their country and present his work. Thanks to the support accompanying the invitation, he was able to spend substantial time in Italy, and he subsequently received recognition and support for his writing in Portugal. Marqués composed the collection of poems now entitled Óbitos (Obits) between 2003 and 2007, writing primarily in those two European countries. He now resides in Spain, where he works at a psychiatric hospital.

In 2003, Italy’s International Writers’ Parliament invited Pedro Marqués to travel from Cuba to their country and present his work. Thanks to the support accompanying the invitation, he was able to spend substantial time in Italy, and he subsequently received recognition and support for his writing in Portugal. Marqués composed the collection of poems now entitled Óbitos (Obits) between 2003 and 2007, writing primarily in those two European countries. He now resides in Spain, where he works at a psychiatric hospital.

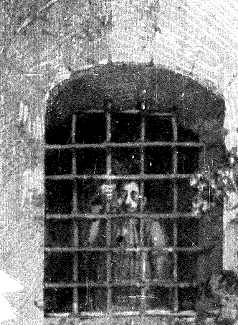

As a doctor with professional experience in mental health, Marqués has long been reflecting on classifications of illness and wellness, and the ways in which societies imagine treatment. Reviewing more of his poetry, readers will find frequent reference to spaces such as hospitals and asylums, as well as a tendency to note perspectives through which bodies are analyzed by different sorts of professionals, among them scientists.

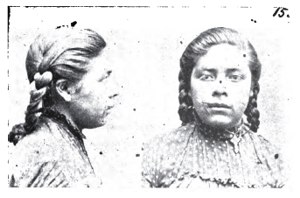

The following selection of poems from Obits taps into Marqués’ long-standing interests in medicine, power, and the marginalization of peoples. They also draw on his more recent readings in Cuban history of the late nineteenth century, although he tells me that he did not originally plan to apply those to the composition of poetry. Marqués finds himself particularly drawn to the issue of criminality and therefore to the “crónica roja,” or the nineteenth-century press accounts focused on crime and criminals. In recent years he has also been reading a great deal about the phenomenon of suicide.

In one of our conversations Marqués jokingly characterized himself as a failed sociologist. More seriously, he takes a sustained interest in how violence functions as an organizing thread in societies past and present. He enjoys archival research, the first-hand encounter with a document. Yet he is less interested in the surface “facts” that documents purport to present than in the potential for a reader to envision shadowy presences that are only suggested by documentation – that is, imagining the suppressed subjects and marginal lives at which an archive only hints.

Perhaps this is his most utopian vision for what the creative action of poetry can offer us. Other forms of utopia being conspicuously absent from these poems, despite the ubiquitous association of islands, and Cuba in particular, with utopia in so much literature. To this speculation I must add, however, that Marqués is careful to say that he does not see poetry as offering redemption from that violence whose contours it traces.

The title of his collection, Óbitos, points to mortality of various kinds. Literal death is clearly present, as in the catalogue of deaths in “Crónica” (“Chronicle”). I would suggest that social deaths are also present for many of the people represented here, for whom some confining social and legal status prevents access to fuller lives as citizens. To translate the word “óbitos,” I considered the colloquial option of “deaths” and the more elaborate but awkward sound of “demises.” In the end I settled on a term that arrived in English by way of French: “obit” is still classified in some dictionaries as a foreign term operating in English. It remains unusual enough to catch the eye.

deaths in “Crónica” (“Chronicle”). I would suggest that social deaths are also present for many of the people represented here, for whom some confining social and legal status prevents access to fuller lives as citizens. To translate the word “óbitos,” I considered the colloquial option of “deaths” and the more elaborate but awkward sound of “demises.” In the end I settled on a term that arrived in English by way of French: “obit” is still classified in some dictionaries as a foreign term operating in English. It remains unusual enough to catch the eye.

The title of this collection does need to be charged with its own sense of drama. The short poem “también tú” (“and also you”), which implicates the reader in the world of the poems, asks us to dwell on the term “óbitos”: “fíjate qué / palabra” (“look, what / a word”). Too bland a rendition of the term would fail this poem in its English incarnation.

For the translator another risk is to adopt a term that might be excessively indirect or obscure, which can mute the poem. Fortunately the collection’s title gives the translator another option which is neither dull nor silencing: “obits” is not as colloquial a term in English as “deaths,” but the related term “obituary” is utterly common, since it is the name for the genre of newspaper writing that recognizes a death in the community. “Obit.” has come to be accepted as its standard abbreviation. Given Marqués’ fascination with the press, and with the public status of people branded as criminal or insane or both, I’m pleased to rely on language from public announcements for the deployment of the translation.

If the resulting translation “obit” conjures adequate meaning for most readers via its association with the press, some may recognize another rich layer of meanings in the shared root: “from Latin obitus going down, setting, death” (Oxford Essential Dictionary of Foreign Terms in English). As an appropriated foreign term used in English, “obit” also initially referred to memorial ceremonies. This history of the word offers another fine way to think about Marqués’ approach to poetry, this time in terms of how ethics meets with performance in rituals addressing death. Can we call these poems, which mark an individual’s points of interface with records of violence and suppression, a form of mourning? or are the poems doing something else?

In his collection as a whole, Marqués has blended his source material from press accounts with moments inspired by other writers. Here I’ll briefly note examples that may be of interest to readers. José Lezama Lima’s “Oda a Julián del Casal” (“Ode to Julian del Casal”) threads into “Chronicle” with a slight variation on Lezama’s phrase “ansias de aniquilarme sólo siento” – itself a phrase extracted from an earlier poem by Casal, “Nihilismo.” Elsewhere Marqués cites Buchner’s Lenz more openly; he is interested in the title character, who embodies the energy and creativity of madness until a crucial moment when that activity comes to a stop. Kafka makes an appearance to state, “For the last time psychology.” Marqués’ woman from Ardennes, meanwhile, is a figure from the history and texts of the French Revolution: Théroigne de Méricourt was institutionalized as a madwoman. Jean-Étienne Dominique Esquirol carried out an autopsy on her body after her death, as the hair and nails continued to grow on the cadaver.

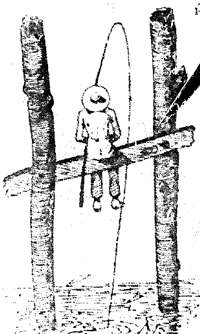

In several cases, our conversation influenced me to choose options for these translations that aren’t entirely literal. In “Acerca de un documento” (“About a document”) I selected terms that emphasize the importance of sugar plantations to the scene as a whole. Marqués notes that twin powers (the sharp edges or blades of the poem) supported the plantation economy, a system organizing much of Cuban society in the nineteenth century: the power of the owners themselves, and the power of the church.

The end of “Chronicle” offers an interesting confluence of factors related to the power of the sugar plantation and its effects on the populace it organized:

el que echó la mora al agua

atada al cepo -dicen-

desde la eternidad

[the one who tossed the slave into the water

still in the stocks– so they call her:

negress in eternity]

This compact set of lines presents a series of challenges to the translator: melded race, gender, and philosophical categorizations comprise the poet’s take on language and history. First, the Spanish terms “mora” and “atada” are gendered feminine, so the gender has to be worked into the English somehow, even though English does not normally allow for as much efficient gender coding. Second, Marqués notes that “mora” should not be rendered as “Moor.” In the context of the nineteenth-century Cuban sugar economy, “la mora” indicates a more immediate African heritage attributed to the woman – and this label, defined by slavery in the Caribbean, dictated that someone could think her status meant she could be thrown into the water in stocks. Thirdly, the arrival at the line “desde la eternidad” embodies one of those connections that Marqués finds with other writers. He explains that he gestures to “Rimbaud, whose line Deleuze liked so much: ‘I am black [negro] from eternity.’ Slave women are designated slave women from eternity and, at times, they appear to have always been in stocks . . . in sum: a metaphor for eternal condemnation” (email, 17 November 2009; my translation). The metaphor foregrounds the consequences of formal and informal classification, the violent deployment of concept upon actual bodies and lives.

Some but not all of these selected poems from Óbitos were published in the original Spanish within a recent anthology of Marqués’ poetry: Cabeças e outros poemas (bilingual Spanish/Portuguese edition, selection and translation by Marcelo Flores; São Paulo: Hedra/Sibila, 2008). In addition to the source cited below, email exchanges with the author provided me with much of the information I’ve presented here, as did a followup meeting with Marqués in Madrid on November 28, 2009. I would like to thank him for his generosity: given that his poetry is grounded in such specific references, his clarifications and emphases were essential to both the translations and this introduction. They were also helpful as I considered how to conjure his points of reference for readers who might be unfamiliar not only with his own work, but with some of the people, places, events and/or clustered associations around which his poetry revolves.

***

"Obit, noun." The Oxford Essential Dictionary of Foreign Terms in English. Ed. Jennifer Speake. Berkley Books, 1999. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. Illinois State University. 17 November 2009 <http://www.oxfordreference.com/views/ENTRY.html?subview=Main&entry=t33.e4817>

POEMS from OBITS (2003-2007) * POEMAS de ÓBITOS (2003-2007)

Pedro Marqués

Tr. Kristin Dykstra

(Chronicle)

the Chinese man they strung up by a foot

at the inlets of San Lázaro

the one whose head stuck

in the filter for the aqueduct on Charles III

the one impaled at Burro

the one impaled at Burro

Hill the one cut to pieces

near the iron rails

the last peon

all those people in their predicaments

all those people in the shadow

of: what

the one who drank from the (public) flower of the urinals

who slit the Count’s throat and was taken for a madman

then invented a device to take his own life

(Gears-of-Perpetual-Machinery)

the executioner who got in through the hole in the wall

the one who cut the face of Father Claret

in a fit of rapture following mass

the shrouded man who passed him

the rustic blade the one who deployed

the poison that leaves no

trace (Gallic rose)

all those people in their predicaments

all those people in the shadow

of: what

Bompart’s lover

captured at the Hotel Roma

thirty yards from the Church of Christ

the one who cried out – before the twelve-year-old girl with olive skin

and the maddened father hung from a hook –

craving self-annihilation I know the one who survived

the turning of the press but not the legionella

the one who threw acid at Gomez the trader

next to the altar the one who lit the timber

the one who tossed the slave into the water

still in the stocks– so they call her:

negress in eternity

all those people in their predicaments

all those people in the shadow

of: what

(Crónica)

el chino que colgaron de un pie

en las Caletas de San Lázaro

el que se metió de cabeza

en los filtros de Carlos III

el empalado de la loma

del burro el trucidado

del camino de hierro

el último peón

toda esa gente en aprieto

toda esa gente a la sombra

toda esa gente a la sombra

de qué

el que bebió la flor (pública) de los urinarios

el que degolló al Conde y lo dieron por loco

y después inventó un aparato para matarse

(Engranaje-Sin-Fin)

el verdugo que entraba por el boquete

el que le cortó la cara al Padre Claret

en un raptus luego de misa

el embozado que le pasó

la chaveta el que empleó

el veneno que no deja

traza (Rosa francesa)

toda esa gente en aprieto

toda esa gente a la sombra

de qué

el amante de la Bompart

apresado en el Hotel Roma

a 30 yardas de la Iglesia de Cristo

el que gritó -ante la trigueñita de los doce años

y el padre enloquecido colgado de un gancho-

ansias de aniquilarme siento el que soportó

el giro del tórculo pero no a las legionelas

el que arrojó vitriolo al negrero Gómez

junto al altar el que prendió yesca

el que echó la mora al agua

atada al cepo -dicen-

desde la eternidad

toda esa gente en aprieto

toda esa gente a la sombra

de qué

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

WOMAN FROM THE ARDENNES. SECOND EXERCISE.

They shaved everyone’s head but hers. The hair and nails, not that discolored cerebrum, nor those carotids with the diameter of a feather: her final belongings.

When she leaned out the hospital window to shout:

“Leveling.”

She was already dead. But the cry she gave – ragged bird – rang out in the Bosphorus. How was it not going to snap the thread if they shaved even the grass and turned it to a path, as M. Esquirol gave signals with flags and Saint-Just, so deaf:

“Justice doesn’t mix with saintliness.”

Then the return by car to Liège.

Where was she going to be?

LA ARDENESA. SEGUNDO EJERCICIO.

Raparon todas las cabezas, menos la suya. El pelo y las uñas y no ese cerebro descolorido, ni esas carótidas del diámetro de una pluma: sus últimas pertenencias.

Cuando asomó por la ventana del pabellón para gritar:

-Nivelamiento.

Ya estaba muerta. Pero su grito -ave greñuda- repicó en el Bósforo. Cómo no iba a quebrar la cinta si hasta el césped raparon hasta convertirlo en sendero,

mientras M. Esquirol hacía señas con banderitas y Saint-Just, tan sordo:

-No se junta justicia y santidad.

Luego el regreso en coche, a Lieja.

¿A dónde iba a ser?

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

and also you

in the obit (look, what

a word) of History

through a

veil watching

también tú

en el óbito (fíjate qué

palabra) de la Historia

por un velo a-

somado

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

(odometer)

that which falls (for example) from on high

from a cardboard sky

next to the ploughshare

in Lenz

has its horizontality

(cuentapasos)

lo que cae (por ejemplo) desde lo alto

de un cielo de cartón

junto a la rejilla de arado

en Lenz

tiene su horizontalidad

------------------------------------------------

(Neptune’s obscured eye)

in measureless barbarism

some chop off the others’ hair

at what segment of the bone

are they

in what bracket of a concept

still

staggering around

(el ojo negro de Neptuno)

en barberías insondables

pelándose los unos a los otros

en qué sección de hueso

están

en qué tramo de concepto

aún

dando tumbos

--------------------------------------------------------------------

“for the last time psychology,” they say

he said descending the stairs in starts

(in the brothel) the vomit came just before

the fall into the chorus girl’s arms

“por última vez psicología”, dicen

que dijo bajando a trompicones la escalera

(del prostíbulo) el vómito a punto

hasta caer en brazos de la corista

---------------------------------------------------------------------

it has moorings

and tight

reins

tie it

tight

tight

in an iamb with five

of these feet

and drag it along

to the darkened

house of the non

baroque

(that is if

you can)

poetry’s

got its

thing

tiene amarres

y riendas

cortas

amárrala

corto

con un yambo de cinco

pies

y arrástrala

a la casa

oscura del no

barroco

(esto si

puedes)

poesía

tiene su

cosa

------------------------------------------------

ABOUT A DOCUMENT

what was there – you asked – between

the roundhouse and the storeroom,

just white space? just the carriage house

and the swine market? just miasmas

—populations? in any case

between the two filed edges of the plantation machine

what was there – you asked – and I think

I answered: any

number

ACERCA DE UN DOCUMENTO

qué había -preguntaste- entre

la casa de máquinas y el almacén

¿sólo brecha blanca? ¿sólo la cochera

y el rastro de cerdos? ¿sólo miasmas

-poblaciones? en cualquier caso

entre las dos cuchillas del ingenio

qué había -preguntaste- y creo

que te respondí: cualquier

cantidad