Salianka in CUCS: Revisiting the Soviet Past at the ‘Russian’ Book Fair in Havana

Jacqueline Loss, University of Connecticut

The rehearsal of Cuba as a Socialist bloc junkyard has entered a new stage altogether. It is almost standard for Cubans to delineate the Soviet physical remains on the island before they dig deeper into a discussion of the Soviet legacy. The award-winning exhibit of cutting edge artists in 2007, Vostok: Proyecto de exposición colectiva (Vostok: A Collective Exhibition Project), re-codified a workshop of spare parts in Havana into a radical visual arts experiment, challenging that gesture to recite the list while, at the “Último Jueves” (Last Thursday) roundtable of the journal Temas in May 2009 (also in Havana), the esteemed critic and translator Zoia Barash began her presentation on the influence of Soviet cinematography in Cuba with the phrase “Russian traces exist, and at times, they are perceived not only in the form of nostalgia for Russian meat or for the Aurika washing machine.” It was an anecdotal nod to which Julio Travieso, another respected translator who was in the audience, added “vodka” and “Russian women.” (1)

Enrique Colina’s 52-minute documentary Les Russes à Cuba (2008) does a great job at picking up on the plethora of consumer items from the Soviet Bloc that the masses continue not only to recall, as in those cans of Russian meat and powered milk, but also to use, albeit against all odds, as the documentary’s magnificent close-ups of an Aurika washer and Orbita fan prove. One could easily imagine these objects as being the point of a departure for yet another (Goodbye, Lolek, being the first) perhaps more light-hearted Good Bye, Lenin! Cuban style. However, the rejection of Colina’s Cuban version of the documentary entitled Los bolos en Cuba y una eterna amistad by the commission for the 2011 Festival of New Latin American Cinema supposedly on account of its being too long and in its finding itself within a too large pool of submissions suggests that the documentary had something else. (2) And that something else might be attributed to a use value, not merely light-hearted wink at an earlier mode of Communism.

Toward the end of the French version of the documentary, Colina glimpses at the denouement of the “felices ochenta” (happy 1980s) through examining an installation by Lázaro Saavedra and Rubén Torres Llorca within the 1989 exhibition entitled “Una mirada retrospectiva” (A retrospective gaze), within which Elpidio Valdés, the hero of the cartoons who fought against Spanish colonialism, and the matrioshkaare linked, not by the embrace of solidarity, but rather by an intravenous catheter, pumping blood into Elpidio. In fact, what makes Les Russes à Cuba provocative are its final scenes in which Saavedra speaks about this installation as Los Van Van’s song “Se acabó el querer” (Wanting is done away with) plays, and a young and modern-day Cuban girl dances in front of a mural of Cuban and the Soviet flags, with cuts of old footage from the years of the Soviet-Cuban solidarity in the background. At once, Saavedra cuts the catheter in the foreground. (3)

A rather fairy tale–like version of the Soviet-Cuban union can be found in Daniel Díaz Torres’s Lisanka (2009), produced by Spain’s Ibermedia, the ICAIC, and Mosfilm Studios, the first result of another agreement formed in 2008 between Russia and Cuba. (4) Using the stylistic strategies of fables –an omniscient narrator, animation, archetypical characters who live in a picturesque village– this feature neatly assigns the 1962 Missile Crisis a backseat in order to focus on the more sentimental consequences of the arrival of a young romantic Soviet to a nearby military base and his interrupting the love triangle among an young ebullient Cuban lady, Lisanka; her Revolutionary lover; and her reactionary lover.

The new balanced climate of Cuban revisions of the Soviets must be understood as dimensions of recent strategic collaborations, of which the 2008 cinematographic accord is only one of many. They include a series of visits of Russian officials (Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev in 2008 and the Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov in 2010), the inauguration  of the Russian Orthodox Church in 2008, and a Russian oil company’s exploration of offshore oil concessions in 2011.

of the Russian Orthodox Church in 2008, and a Russian oil company’s exploration of offshore oil concessions in 2011.

However, some things still escape choreography. By far, the act of memorialization that best displays the multiple loyalties, complexities, contradictions, and opportunisms that come into play around the topic of Cubans’ memories of the Soviet Bloc was the 2010 International Book Fair in Cuba wherein Russia was the guest of honor. On the grounds of the Morro Castle and La Cabaña Fort, unique material installations in the form of replicas (as opposed to ruins) took temporary root. Perhaps none was comparable to the unusually placed replica of a kind of rocket from the CCCP (the acronym for Soyuz Sovetskikh Sotsialisticheskikh Respublik or the USSR) that contained within a photograph of the cosmonauts Arnaldo Tamayo and Yuri Romanenko (fig. 1). This ambiguous object (fig. 2) was positioned in the back of the “Russian”–themed restaurant on the fairgrounds and within the visual panorama of the crosses of a number of churches. Had this replica of greatness and solidarity been situated more centrally, it could have been a major highlight of the theme park.

Fair in Cuba wherein Russia was the guest of honor. On the grounds of the Morro Castle and La Cabaña Fort, unique material installations in the form of replicas (as opposed to ruins) took temporary root. Perhaps none was comparable to the unusually placed replica of a kind of rocket from the CCCP (the acronym for Soyuz Sovetskikh Sotsialisticheskikh Respublik or the USSR) that contained within a photograph of the cosmonauts Arnaldo Tamayo and Yuri Romanenko (fig. 1). This ambiguous object (fig. 2) was positioned in the back of the “Russian”–themed restaurant on the fairgrounds and within the visual panorama of the crosses of a number of churches. Had this replica of greatness and solidarity been situated more centrally, it could have been a major highlight of the theme park.

The ambiguity as to whether to call the theme park “Russian” or “Soviet” has not perished with the disintegration of the Soviet Union. On the periphery of the grounds, the installation could very easily have passed for a ruin. That said, it is difficult to assess this “found object” and not wonder who was behind such an idea. Depending on the answer, it could be a symptom of Russian imperial nostalgia or an  expression of Cuban aspirations for the future laid out through a visual ode to a previous solidarity.

expression of Cuban aspirations for the future laid out through a visual ode to a previous solidarity.

Before examining the Book Fair’s “Russian” restaurant, let us consider the actual restaurant presented in Zoe García’s documentary Todo tiempo pasado fue mejor (2008). The story of Havana’s Moscú restaurant, which opened in 1974, two years after Cuba’s entrance into the COMECON, and burned down in January 1990, is the subject around which the documentary’s interview of four intellectuals and artists about the topic of the Soviets in Cuba is structured. The premise resembles the shifting perspectives on the incipient Revolution that were prompted by the arson attack on the glamorous department store El encanto (The Enchantment) in April 1961. (5) Moscú restaurant, which once showcased the triumphs of the USSR’s kitchen, is a perfect metonymy for Cuba’s relationship with the Soviet Bloc. The title of the documentary, tellingly scripted in Latin letters in a Cyrillic font, is portrayed as a national shield crowned by the PCC (the acronym for Partido Comunista de Cuba) and supported below by CCCP. For a whole minute, spectators can study the shield and listen to a conventional version of the song “The Musicians of Bremen.” Todo tiempo pasado fue mejor ends with Ciro Díaz, the guitarist of Porno para Ricardo, playing that same song –the one that Ernesto René rendered brilliantly in the 2001 music video, which was retrieved by Asori Soto in the 2005 Goodbye, Lolek! and again by René and Betancourt’s 2006 documentary 9550. Of the song’s repetition one may conclude that the Muñequitos Rusos Generation either suffers from a lack of originality or, more likely, that no other song captures quite as well the anxieties of that generation to not end up merely as the characters of Soviet Bloc animation.

The documentary’s establishing shots render the disorientation characteristic of aging inhabitants whose world changed before their eyes. Gray, stormy skies above buildings that look as if they were bombed serve to transport Havana to parts of the former Socialist Bloc farther east, yet close–ups showing Havana’s residents trying to indicate the location of Moscú restaurant undoubtedly place the documentary in Cuba. The documentary’s focus on a restaurant and its culinary offerings distract viewers from some of its more problematic remarks, such as the warning by film critic Gustavo Arcos: “The Soviet Union failed for many reasons. But attention: the reasons the Soviet system failed are the same reasons that could make our own system fail because it is structured—I repeat—on the same schemes, the same principals.” Cubans act out nostalgia toward the Soviet commodity culture and yet simultaneously critique the foundations of Soviet ideology, some of which remains well anchored in Cuba.

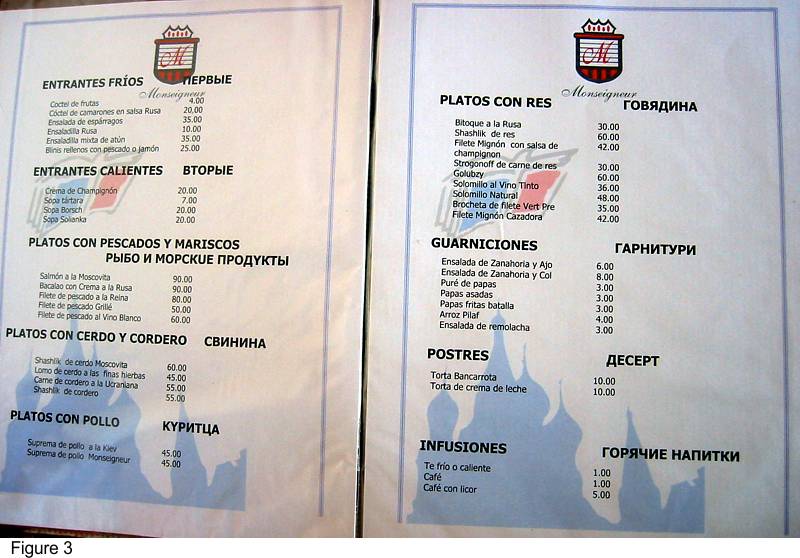

It is within this contradiction that we must consider the “Russian” restaurant, re–created solely for the purposes of the 2010 International Book Fair. The menu (fig. 3), like the majority of the products sold at the fair, was priced in national currency and featured tartar soup, borsch, salianka, sashik, as well as slew of other archetypical meals, replicated in post–Soviet Cuba with the flavors of nostalgic Cubans in mind. No matter that consuming Russians and other foreigners with access to the same menu in the capitalist world largely did not recognize the dishes being served, and that, on more than one occasion, Cuban clients complained that the food would have been more authentic had those “matrioshka” remaining on the island prepared it. The seasoning lacked some of the ingredients to make it taste Russian, but fortunately, many of the diners’ memories were sufficiently “informed” so that the missing ingredients did not significantly disturb the overall set design. The atmosphere was pleasant and even reminiscent of the 1980s heyday of equanimity.

The confusing nature of the Book Fair rested on the desire by Russians and Cubans alike, first, to bring to light pre–Soviet ties of Cuba to Russia in the nineteenth and early twentieth century; second, to rescue from the Soviet mirage the nineteenth –and twentieth– century Russian classics; third, to uphold the great aspects of the Soviet period; and fourth, to distinguish between the old Soviets who served as Cuban big brothers and the new Russians who have moved far away from the Soviet period, all of which serve to highlight the possibilities of future cultural collaborations.

Corresponding to a similar impulse of historicizing the Russian–Cuban friendship seen in Alexander Moiséev and Olga Egórova’s book Los rusos en Cuba is the publication La cultura rusa en José Martí (2010) by Luis Álvarez Álvarez. An even more remarkable dimension of the quest for a renewed friendship on the part of the Russians is the fact that in 2010, their Writers’ Union awarded the Cuban Jaime Abelino López García the Gold Pen prize for his translation into Russian of a chapter of Álvarez Álvarez’s book. (6) In 1992, some eighteen years prior to these occurrences, at the time of the restructuring of the Cuban “autonomous” constitution, a book about Russian traces within the nineteenth–century apostle would have been almost inconceivable. “As is obvious,” Álvarez Álvarez’s analysis concludes, “the Russian culture was for Martí a magnetic pole of attraction: poets, novelists, scientists, plastic artists, playwrights, monarchs and politicians, but also its language, its popular customs, its folkloric heritage magnetized his attention.” (7) For Spanish American modernists, foreign cultures were indeed exploited, and Álvarez Álvarez situates Russian culture within this universal panorama; nevertheless, the tremendously convenient timing of this scholarly exploration is impossible to deny.

Translation is of utmost importance to the project of new ties, as it was during the Soviet period. Not only did López García impress the Russian judges with his fluency in his nonnative tongue in 2010, but one year prior, this purportedly nostalgic admirer of all things from the former Soviet Union –where he had studied mechanical engineering–actually won the Gold Pen’s honorable mention for his translation into Spanish of popular tales about the Mari people in the former Soviet Union. What is particular about the case of López García is his own desire to transmit knowledge of Soviet diversity to the young people of Cuba, as reflected in the volume’s title, which pays homage to his daughter, Laura: Cuentos para Laura: Relatos populares maris (Stories for Laura: Popular Mari Tales), a book that can be understood as a flashback to López García’s own youth populated by the kinds of tales published in Cuban–Soviet editions from the 1970s and 1980s.

Like the exploration of Martí’s Russian influence in two languages, the publication of numerous translations of Russian nineteenth –and twentieth– century classics into Spanish signals the resuscitated political vigor of Russian culture in Cuba. The anthology Cuentos de grandes escritores rusos (Stories of Great Russian Writers), edited by Julio Travieso and published by Arte y Literatura in 2009, includes stories by Alexander Pushkin, Nikolai Gogol, Mikhail Lermontov, Ivan Turgenev, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Mikhail Saltykov-Schedrin, Leo Tolstoy, Boris Pilnyak, Eugene Zamiatin, Nikolai Leskov, Vladimir Korolenko, Anton Chekhov, Maxim Gorky, Alexsandr Kuprin, Ivan Bunin, Isaac Babel, Mikhail Bulgakov, Vladimir Nabokov, and Mikhail Sholokhov, among many others. The collection corresponds precisely to the new trend. With the exception of the translations by Travieso, all others are anonymous.

Although the volume’s prologue (another contribution by Travieso) is far from extensive, it does point out a few central issues whose significance goes beyond the volume. Travieso describes the process of increased institutionalization between 1934 and 1953 that resulted in prescriptions of how to write “grey and flat literature.” (8) That period, he continues, was preceded by the Golden and Silver Age of Russian literature and followed by transitional years. An example of how the more problematic of writers is treated by Travieso is his explanation of his selection of, among other realist writers, Sholokhov, whom he calls a practitioner of “psychological realism” as opposed to “socialist realism.” (9) Although, as Travieso states, Sholokhov did win the Nobel Prize in 1965, he was also given the Stalin Prize in 1941, something that is not mentioned in the prologue. Travieso’s treatment of Sholokhov in his collection, along with the Soviet writer’s resuscitation at the 2010 Book Fair –as can be seen by the fair’s exhibition in honor of the 105th anniversary of his birth (fig. 4)– is a way of securing that Sholokhov remain every bit a hero in the international sphere as he once was.

issues whose significance goes beyond the volume. Travieso describes the process of increased institutionalization between 1934 and 1953 that resulted in prescriptions of how to write “grey and flat literature.” (8) That period, he continues, was preceded by the Golden and Silver Age of Russian literature and followed by transitional years. An example of how the more problematic of writers is treated by Travieso is his explanation of his selection of, among other realist writers, Sholokhov, whom he calls a practitioner of “psychological realism” as opposed to “socialist realism.” (9) Although, as Travieso states, Sholokhov did win the Nobel Prize in 1965, he was also given the Stalin Prize in 1941, something that is not mentioned in the prologue. Travieso’s treatment of Sholokhov in his collection, along with the Soviet writer’s resuscitation at the 2010 Book Fair –as can be seen by the fair’s exhibition in honor of the 105th anniversary of his birth (fig. 4)– is a way of securing that Sholokhov remain every bit a hero in the international sphere as he once was.

In addition, by deflecting the more critical aspects of the Soviet–Cuban union onto the lesser known pre– and post–Soviet Russian ties, the Book Fair symbolically elongated the span of time that Russians and Cubans were interested in one another. For instance, the Russian embassy published in 2010 a magazine entitled Rusia: Los libros que hacen sabio al hombre (Russia: The Books That Make Man Wise), whose content virtually bypassed recent history: one short piece dedicated to the wealth of the Cuban journal Unión’s cultural collaboration during the Soviet period was placed within the scope of an article about the first Russian teacher in Cuba named Fiodor V. Karzhavin, who had first been published in Granma in the very indicative year of 1989; an exposé on contemporary Russian literature; an excerpt of Travieso’s translation of The Master and Margarita; a text on the monumental nature of Russian libraries such as “la Léninka”; translations of popular Russian stories; and to top it off, a final section of translated Russian jokes, which is perhaps the most significant contribution for understanding the future of Russian–Cuban relations. A caricature of President Obama with a bottle of Vodka in one hand and a cocktail glass in the other appears at the top of the page; below, the phrase “¡Hola, vamos a hacer amistad!” (Hello, we are going to make friends!) This humor ensures that Cuban readers do not to forget that while the United States may possess a friendlier guise these days, it remains ignorant. The Cold War antagonisms endure.

The prolongation of the Soviet–Cuban friendship also affected the Fair’s display of military, diplomatic, and cultural collaboration. For example, a section of the Russian Pavilion was dedicated to the sixty–fifth anniversary of the victory of the Second World War and, in particular, honored Enrique Vilar Figueredo (born in 1925 in Manzanillo, Cuba), the Cuban internationalist who, having enlisted in the Red Army in 1942, died in Poland in 1945 in the fight against fascism. (10) Some photographs commemorating the Soviet–Cuban friendship were never hung, but instead, images of Fidel skiing in Russia, of Fidel meeting the Russian ballerina Maya Plisetskaya, of Fidel holding hands with leaders Nikita Kruschev and Leonid Brezhnev, along with military ships with the word “Cuba” written in Cyrillic, were leaned up against the walls of the exhibition hall.

The 2010 exhibition of “things Russian,” by no means, took on the proportions of the memorable 1976 Soviet exhibition in Havana’s capital building. The Book Fair’s Russian Pavilion was 450 square meters, but indeed 300 publishing houses were present with 3,500 books on display. (11) Computers were on–site with advanced programs to teach Cuban youth about life in Russia. As if this weren’t enough, the Russkiy Mir Foundation donated approximately 30,000 euros to the José Martí National Library to inaugurate a Cultural Center of Russia, one of forty–six similar centers worldwide and the first to open in the Americas, with plans for Nicaragua, Guatemala, and Mexico.

One of the most provocative strategies for ensuring the persistence of Russians in Cubans’ future manifested itself through the efforts at teaching Cuban children about Russian and Soviet history and culture and, at the same time, teaching their parents, members of the Muñequitos Rusos Generation, about their own sentimental ties to the Soviets. They could also have the occasion to become reacquainted with Vladimir Vysotsky’s poetry, translated by Juan Luis Hernández Milian, which was published by Ediciones Matanzas in 2010. Accompanying the display of children’s books from Russia was Vadim  Levin’s collection of handmade models used within Soviet animation. Eduard Uspensky, the author of the stories about Cheburashka and the Crocodile Gena, along with other children’s book authors, pranced their way back into the lives of these once unusual brethren to try to charm the Cuban people, but Uspensky already seemed to be on a different plane in which “time is only money for those with money.” Having expected to address an audience of children, he found himself in front of a group of parents who came of age with his cartoons and were eager to inquire about old topics such as ethics and aesthetics, upon which he appeared not to wish to remark. (12) More than with any other group, it was with the Muñequitos Rusos Generation that the Book Fair engaged in a subtle conversation. The pathway through the Morro Castle to the Children’s Pavilion was decorated with Soviet cartoons, and on the other side, above the children’s stage, was a cut–out of another “castle,” San Basilio Church (fig. 5), placed there almost as if it were the crown in Gertrudis Rivalta’s Quinceañera con Kremlin.

Levin’s collection of handmade models used within Soviet animation. Eduard Uspensky, the author of the stories about Cheburashka and the Crocodile Gena, along with other children’s book authors, pranced their way back into the lives of these once unusual brethren to try to charm the Cuban people, but Uspensky already seemed to be on a different plane in which “time is only money for those with money.” Having expected to address an audience of children, he found himself in front of a group of parents who came of age with his cartoons and were eager to inquire about old topics such as ethics and aesthetics, upon which he appeared not to wish to remark. (12) More than with any other group, it was with the Muñequitos Rusos Generation that the Book Fair engaged in a subtle conversation. The pathway through the Morro Castle to the Children’s Pavilion was decorated with Soviet cartoons, and on the other side, above the children’s stage, was a cut–out of another “castle,” San Basilio Church (fig. 5), placed there almost as if it were the crown in Gertrudis Rivalta’s Quinceañera con Kremlin.

The children’s sections at the Book Fair were the spaces in which the restorative impulses of the Cuban and Russian regimes were most evident. The Russian aspirations for Cuba translated into a stunning exhibition entitled “¡Cuba, eres mi amor!” (Cuba, You Are My Love) that represented Russian children’s fantasies about the island and decorated the walls of the pavilion. After having read some of the most canonical texts of Cuban literature, such as Regino Eladio Boti, Nicolás Guillén, José María Heredia, José Martí, and Juan Marinello Vidaurreta, Russian children painted their imaginations of the island. In many cases, Cuba resembled Gauguin’s Tahiti more than any other island, in the sense that dark–skinned bodies and primitive landscapes reined. Cuban children, in turn, participated in a contest at the book fair entitled “Pintando Rusia” (Painting Russia). Even though the contest, properly titled “Los niños cubanos dibujan Rusia” (Cuban Children Draw Russia) was actually organized by the Russian publishing house, Veselye Kartinki (Merry Pictures), the fact that the announcement for the contest was handwritten, instead of printed out in a polished design in advance, suggesting the discrepant temporalities that are involved within the current Russian–Cuban mirroring. Cuban children’s imaginary of Russia today did not differ so much from the replicas of Soviet families seen in Adelaida Fernández de Juan’s short story “Clemencia bajo el sol” in which a Cuban and a Russian woman become so psychologically intimate that they cross–fertilize over borscht and foreign landscape, or even in Lissette Solórzano’s 2009 photographic exhibition “Erase una vez.. .una Matrioshka," (Once upon a time . . .there was a matrioshka) wherein the exotic former Soviet is incorporated into the domestic space through samovars and religious icons. Snowy landscapes, samovars, matrioshkas, and the San Basilio church somehow effortlessly leaped into the drawings by the contest’s participants.

The makeshift sign also contrasts sharply with the series of postcards, printed on paper of a quality rarely seen in Cuba, released for the Book Fair. The cards representing monumental scenes in Soviet–Cuban history were disseminated to child visitors of the Russian Pavilion. These images with text, written primarily in Cyrillic (as opposed to the Cyrillic font of Todo tiempo pasado fue mejor), resuscitate sites of remembrance, utilizing a classic pedagogical tool of challenging children to stimulate their curiosity. For people who are eager to possess frivolous objects from abroad, these postcards were a hit for their opulence alone. One day in the future these children may come to penetrate the foreign words and discover their meaning.

The children’s extravaganza had many other dimensions, some with messianic overtones. Numerous copies of a 2004 book entitled Niños del milagro (Children of the Miracle) by the journalists Katiushka Blanco, Alina Perera, and Alberto Núñez were placed in a box at the heart of the Book Fair, free for the taking, without having to interact with any vendor or volunteer. The cover features a child’s eyes behind a book entitled Dime como es Venezuela (Tell Me What Venezuela Is Like). Beginning with a short saga about José Martí’s arrival in the Bolivarian Republic in 1881, the book is structured like a travelogue through Venezuela featuring the testimonies of some of the beneficiaries of one of Cuba’s successful humanitarian projects, Operación Milagro (Operation Miracle); that is, it focuses on the real and beautiful stories of Venezuelan children who returned to their country after having been cured of ocular illnesses in Cuba. The book’s rhetoric makes it seem as if Operation Miracle were the realization of a historical solidarity between Martí and Simón Bolivar. Russia distributed for free its own children’s magazine –Veselye Kartinki (Merry Pictures)– to entertain Cubans. At first glance, the Russian messiah was much more traditional: Santa Claus. The explicit message of friendship only slightly transforms those messages from the “olden times” of the Soviet Cuban friendship. Translated by someone with a limited knowledge of Cuban Spanish, indicated by the use of the peninsular second personal plural, the following declaration most relives the prior heroism: “Despite Russia and the precious island of Cuba being far from one another, our peoples have always been friends. Now we want you to get to know our culture, history, [and] country today, and about how Russian children of your age live today.” (13) The message could not be clearer. However, the Russian–Cuban attempt to teach children about the long history is more distanced from the real accomplishments of the two peoples, and instead, represents for Cuban children a cartoon about the Christmas and New Year celebration in Russia, as well as a sampling of watercolor paintings depicting Russians imagining Cuba that seem more like stereotypical portraits than the documentation of any real collaboration.

The other group of Cubans with whom the Book Fair subtly dialogued was a bit older than the Muñequitos Rusos Generation; between fourty five and sixty years old, some of them had traveled to the Soviet Union and served as translators on the Fair’s bilingual panels. They sought to mingle with the Russian visitors, to get closer to the peoples with whom, in retrospect, they felt an affinity that did not have purely nostalgic dimensions, as the words of the renowned Russian–Spanish translator Julio Travieso at the 2009 Temas roundtable convey: “The important thing for me, more than to remember the past . . . are the traces that today’s Russia will leave on Cuba. And I ask myself if some of the thousands of us that went to the Soviet Union will someday be able to return to Moscow, Volgograd, the different regions where we studied.” (14) Svetlana Boym’s categories of “restorative” and “reflective” nostalgia prove useful to analyze these distinct gestures where reflective nostalgia allows for “the meditation of history and the passage of time” and is about “individual and cultural memory,” (15) processes with which Travieso’s words negotiate. “Restorative nostalgia puts emphasis on nostos and proposes to rebuild the lost home and patch up the memory gaps . . . . [Restorative] nostalgics do not think of themselves as nostalgic; they believe that their project is about truth . . . . Restorative nostalgia manifests itself in total reconstructions of monuments of the past.” (16)

But it is Yoss’s outspoken intervention at that very same Temas that uncovered a general strategy of imitation that directly challenged restorative nostalgia:

I believe that this concept of “we hide the truth” still has an extraordinary influence on Cuban society: the politics of verticality is one of the worst traces that the Russian presence has left here. Other traces, one could say, are the military degrees and theory that is studied, and upon which our army operates, and that is based, according to my criteria, on completely dislocated concepts. Does someone remember what the “War of All People” was? It is a strategic concept that has meaning in a country of great territorial extension, that can give itself the luxury of presenting a strategy of elastic backward movement . . . that would not make much sense in Cuba, and that nevertheless, had been mechanically copied from the Russian military manuals, as they copy some other things. (17)

The “War of all People,” a strategy that was construed in 1980 involving all citizens’ involvement in a potential fight against aggression, Yoss remarks, was an example of an unfortunate copy of Soviet military strategies on the island. The “War of all People” was undertaken with the knowhow of Raul Castro who was at that time the Minister of the Cuban Armed Forces and largely responsible for the successful as well as fraught military collaborations with the Soviet Union. To blame the Soviet big brother for the strategy of concealing truths, an accusation which is at least partially valid, is audacious in its admission of the extant remains of the negative dimensions of Cuba’s reliance on the Soviets, and especially so, given that the recent cultural interactions need to be understood as part of an initiative toward new Russian investment on the island.

“Restorative nostalgia” is constitutive of distinct bents within contemporary Cuban rhetoric, but as the Russian book fair and the roundtable evidence, even within the most apparently solidified and legitimized homages to the Soviet past and Russian present, slippages bear witness to a complicated personal and collective memorialization of the Soviets.

Notes

1. See http://www.temas.cult.cu/debates/libro%204/050-069%20rusos.pdf for a transcript of the discussion. The topics covered by the Temas roundtable are worth noting. Diverse in their positions, the panelists—Zoia Barash, Dmitri Prieto Samsonov, the playwright Julio Cid, and Yoss—expounded upon the areas of Soviet inheritance that they know best. Barash discussed cinema; the Russian-Cuban Prieto Samsonov discussed the establishment of an association of Russian immigrants on the island; Julio Cid addressed Soviet influence on artistic pedagogy; and Yoss, the discrepancies between what actually occurred and the language that was used to describe the occurrences, as well as the influence of the Soviets on the artists of his generation. Mervyn J. Bain informed me that a comparable roundtable took place in 2009 in Moscow, entitled "50 Years of the Cuban Revolution (roundtable at the Institute of Latin American Studies)"an event that points to the need to realize a comparative investigation on current Cuban and Russian memorialization. The transcript is published in Latinskaya Amerika 6 (2009), 4-31.

2. See “Enrique Colina: ‘Estamos pagando el precio de una fe muda,’ http://cafefuerte.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=1358&catid=123&Itemid=566, November 25, 2011.

3. Like 9550 (2006) by Ernesto René and Jorge E. Betancourt, Colina’s documentary implements Soviet film to illustrate the strange juxtaposition of Cuban and Soviet sentimental worlds, but evidently Colina is carried out with a larger budget and access to archives, etc.

4. In 2007, prior to the 2008 accord, the Russian Mikhail Kosyrev-Nesterov directed the feature-length Ocean in Cuba, the first such co-production in twenty-five years, about the universal themes of betrayal and love. It premiered in 2008, to largely positive reviews. In 2010, Juan Padrón also brought back on stage the Cuban missile crisis with the animated film Nikita chama boom, which takes a comedic stance toward the boom in childbirths in Cuba in 1963.

5. Sergio, the protagonist of Tomás Gutiérrez Alea’s film Memories of Underdevelopment, reflects on this event early on in the film. This by now classic 1968 movie is about Cuba’s transition from a capitalist system to a revolutionary socialist one.

6. León González, “Feliz camagüeyano,” www.pprincipe.cult.cu/articulos/feliz-camagueyano-por-premio-internacional-con-texto-sobre-marti.htm.

7. Álvarez Álvarez, La cultura rusa, 107.

8. Travieso, Cuentos de grandes escritores rusos, 19.

9. Travieso, Cuentos de grandes escritores rusos, 18,

10. Emphasis on Cuban-Russian military collaborations prior to the Cuban and October Revolutions was put into effect already at the height of the Gray Period. One instance of this is a cartoon in Bohemia from 1970 entitled “Episodios olvidados de nuestra gesta de independencia” (Forgotten Episodes from our Fight for Independence) that features three Russians who fight in Cuba’s war for independence.

11. Although the twentieth Cuban Book Fair in 2011 was dedicated to Cuba’s new allies, the ALBA countries, the Russian Pavilion returned once again.

12. For a chronicle on this unusual encounter, see Mir, “Lo que nos dijo el lacónico papá de Cheburashka,” February 15, 2010, http://www.esquife.cult.cu/primeraepoca/agendaesquife/2010/Feria/03.html.

13.Veselye Kartinki: Edición realizada en el marco del programa “Rusia, país invitado de honor de la XIX Feria Internacional del Libro de la Habana,” Cuba 2010.

14. “Huellas culturales rusas,” http://www.temas.cult.cu/debates/libro%204/050-069%20rusos.pdf.

15. Svetlana Boym, Future of Nostalgia, 49.

16. Boym, Future of Nostalgia, 41.

17. I am quoting what Yoss said at the roundtable, as opposed to the published roundtable transcript at www.temas.cult.cu/debates/libro%204/050-069%20rusos.pdf, since the transcript has been edited.

Images

Fig. 1. Photograph of cosmonauts Arnaldo Tamayo and Yuri Romanenko, part of Ode to the CCCP program in Outer Space, at the 2010 International Book Fair in Havana

Fig. 2. An ode to the CCCP program at the 2010 International Book Fair in Havana.

Fig. 3. Menu of the “Russian” restaurant at the 2010 International Book Fair in Havana.

Fig. 4. “En la tierra del Don Apacible” (In the Land of And Quiet Flows the Don), an exhibition in honor of Mikhail Sholokhov at the 2010 International Book Fair in Havana.

Fig. 5. San Basilio church at Children’s Pavilion of the 2010 International Book Fair in Havana.

Works Cited

Álvarez Álvarez, Luis. La cultura rusa en José Martí. Camagüey: Acana, 2010. Print.

Armenteros, Antonio. País que no era. Havana: Letras Cubanas, 2005. Print.

“Asiste Raúl a la inauguración del Pabellón de Rusia en la Feria del Libro.” Vanguardia. Web. 12 February 2010.

<www.vanguardia.co.cu/index.php?tpl=design/secciones/lectura/portada.tpl.html&newsid_obj_id=18969>

Betancourt, Jorge E. and Ernesto René. 9550. Producciones Por la izquierda, 2006. Print.

Boym, Svetlana. 2001. The Future of Nostalgia. New York: Basic Books. Print.

“Exposición soviética: 15 mil cuadrados metros de la vida, la técnica y la ciencia socialistas”. Bohemia 68.27 (1976). 56–57. Print.

Fernández de Juan, Adelaida. “Clemencia bajo el sol.” Nuevos narradores cubanos. Ed. Michi Strausfeld. Madrid: Siruela, 2000. 77–87. Print.

Good Bye, Lenin! Directed by Wolfgang Becker. X-Filme Creative Pool. 2003. Film.

Goodbye Lolek! Directed by Asori Soto. Producciones Aguaje. 2005. Film.

León González, Yanetsy. “Feliz camagüeyano por premio internacional con texto sobre Martí.” Príncipe: Portal de la Cultura de Camagüey, Cuba. Web. 16 November 2010.

<www.pprincipe.cult.cu/articulos/feliz-camagueyano-por-premio-internacional-con-texto-sobre-marti.htm>.

Memorias del subdesarrollo. Directed by Tomás Gutiérrez Alea. ICAIC. 1968. Film.

Mir, Andrés. “Lo que nos dijo el lacónico papá de Cheburashka.” Web. 15 Feb. 2010.

<www.esquife.cult.cu/primeraepoca/agendaesquife/2010/Feria/03.html>

Moiséev, Alexander and Olga Egórova. Los rusos en Cuba. Havana: Abril, 2010. Print.

Pérez, Silvia. “Cuba en el CAME. Una integración extracontinental.” Nueva Sociedad 68 (1983): 131–139. <http://www.nuso.org/upload/articulos/1108_1.pdf.On-Line>Article 14 pp.

René, Ernesto René. “Los músicos de Bremen.” 2001. <www.youtube.com/watch?v=lkqDDlUFPMo>.

Rodríguez, Reina María. “Nostalgia.” Trans. Kristin Dykstra. Caviar with Rum. New York: Palgrave, 2012. Print.