Memory and Mourning in Contemporary Latin American Literature: A Reading of Claudia Hernández’ De fronteras

Yansi Pérez, Carleton College

January 16, 2007 marked the 15th anniversary of the signing of the peace accords in El Salvador. Much was written about the anniversary but I was especially struck by what Fernando Umaña, a theater director, said in an article about the role of artists in the forging of the peace. Umaña focuses on the ghosts that still linger, approximately half of his generation that perished during the conflict. He says, “Son los fantasmas. Los sueño, los recuerdo” (n.p.). It is no coincidence that he is reminded of the ghost of Hamlet’s father who commands him to remember, “Adieu, adieu, adieu. Remember me.” With many years after the signing of the accords and with many ghosts that continue to haunt the nation and its fragile peace, Umaña speaks of the only three survivors of a school theater group he participated in: “Sé que tengo un compañero que tiene una pierna de prótesis, también es fuerte ¿no? De los tres vivos uno está fuera del país, yo estoy acá y el otro tiene una prótesis. Somos dos y medio, digamos. Somos tres. ¿Entiendes el sentido de los ‘medio muertos’ de Roque Dalton? …[H]ay una frase, que después del 32 los salvadoreños somos medio vivos y medio muertos.” (n.p. interview El Faro newspaper). Umaña’s words are exemplary of a nation fragmented in many directions: by a war that resulted in approximately 2 million of the nation’s citizens scattered throughout the world, by a peace accord that left many crimes unpunished and by the violence which tore people apart,

January 16, 2007 marked the 15th anniversary of the signing of the peace accords in El Salvador. Much was written about the anniversary but I was especially struck by what Fernando Umaña, a theater director, said in an article about the role of artists in the forging of the peace. Umaña focuses on the ghosts that still linger, approximately half of his generation that perished during the conflict. He says, “Son los fantasmas. Los sueño, los recuerdo” (n.p.). It is no coincidence that he is reminded of the ghost of Hamlet’s father who commands him to remember, “Adieu, adieu, adieu. Remember me.” With many years after the signing of the accords and with many ghosts that continue to haunt the nation and its fragile peace, Umaña speaks of the only three survivors of a school theater group he participated in: “Sé que tengo un compañero que tiene una pierna de prótesis, también es fuerte ¿no? De los tres vivos uno está fuera del país, yo estoy acá y el otro tiene una prótesis. Somos dos y medio, digamos. Somos tres. ¿Entiendes el sentido de los ‘medio muertos’ de Roque Dalton? …[H]ay una frase, que después del 32 los salvadoreños somos medio vivos y medio muertos.” (n.p. interview El Faro newspaper). Umaña’s words are exemplary of a nation fragmented in many directions: by a war that resulted in approximately 2 million of the nation’s citizens scattered throughout the world, by a peace accord that left many crimes unpunished and by the violence which tore people apart, sometimes literally, and left them without limbs. He insists on the problematic relationship that exists between remembering, forgetting and forgiving. The ghosts that still haunt him demand him to remember, “‘No olvides’, le dice la sombra a Hamlet’” (n.p.). But Umaña also maintains that no crime should ever be left unpunished and declares, “…perdonar no es tan fácil. Es más fácil olvidar” (n.p.). The tension between paying the proper respects to the dead and forging a peace based on reconciliation which, for many, means forgetting, has proven to be a considerable task for the nation. The past that concerns Umaña, however, is not one that is dead or buried. Like the ghosts that haunt Umaña and the rest of the Salvadoran nation, it is a past that comes back, that refuses to be silenced, that demands justice and that wants to remain a presence in the present and the future.

sometimes literally, and left them without limbs. He insists on the problematic relationship that exists between remembering, forgetting and forgiving. The ghosts that still haunt him demand him to remember, “‘No olvides’, le dice la sombra a Hamlet’” (n.p.). But Umaña also maintains that no crime should ever be left unpunished and declares, “…perdonar no es tan fácil. Es más fácil olvidar” (n.p.). The tension between paying the proper respects to the dead and forging a peace based on reconciliation which, for many, means forgetting, has proven to be a considerable task for the nation. The past that concerns Umaña, however, is not one that is dead or buried. Like the ghosts that haunt Umaña and the rest of the Salvadoran nation, it is a past that comes back, that refuses to be silenced, that demands justice and that wants to remain a presence in the present and the future.

The politics of memory and mourning and the manner in which we remember is the focus of my essay. This paper consists of three parts. In the first part, I will study the politics of memory through two texts that examine this issue: Idelber Avelar’s The Untimely Present: Postdictatorial Latin American Fiction and the Task of Mourning and Rubén Ríos Ávila’s La raza cómica del sujeto en Puerto Rico. In my reading of these texts, I propose a different notion of memory where mourning, irony, laughter and sarcasm all work with each other and I will trace a literary genealogy of how this mix has been presented in various Latin American texts. I will first examine Memórias póstumas de Brás Cubas by Machado de Assis and Tres tristes tigres by Guillermo Cabrera Infante. Finally, I will demonstrate the importance that this type of exercise has for the study of memory in contemporary Salvadoran literature through my analysis of Claudia Hernández’ short stories in De fronteras.

Due to the great protagonism that studies of memory have had in contemporary Latin American literature, any attempt to propose a different way of reading memory or new texts to read and include in this tradition requires a critical approach to memory not only in its thematic and formal dimension but also in its dimension in the realm of the affects. One has to review how the politics of memory have been conceptualized in Latin American studies. The critical reading of this tradition and the way that I distance myself from it will serve as a way to get us closer to the texts that constitute the corpus of this essay. These texts permit us to imagine a different exercise of memory where mourning alternates with irony, humor and parody. My study proposes the following theory: to be able to inherit in the periphery, the work of mourning is not sufficient, it has to be complemented and at times subverted by irony.

To write about the various studies of memory in Latin America would require a whole book, not just an essay. I will, therefore, limit my study to two texts which I find decisive to understand memory in Latin America and its cultural importance. The first text is The Untimely Present. Postdictatorial Latin American Fiction and the Task of Mourningby Idelber Avelar. I choose this text because of the importance the cases of Chile and Argentina have had in the theoretical presentations about memory in the last few years and also because of this book’s enormous influence in this area of study. The second text is by Rubén Ríos Ávila La raza cómica del sujeto en Puerto Rico. I focus on this book because the author establishes a juxtaposition between mourning and laughter that I find extremely useful in my own study. The marginal position that Puerto Rican literature occupies (much like Central American literature) in Latin American studies allows Ríos Ávila to have a critical perspective about this area of study.(1)

Memory and Affects

How is restitution possible or conceivable when that which is to be restituted belongs in the order of affect? (ix). With this question Idelber Avelar begins his text The Untimely Present which studies postdictatorial fiction in Latin America and the task of mourning. The text by Avelar attempts to think the inherent value of memory. According to him, memory cannot be reduced to either its use value or its exchange value. Memory has intrinsic value that he names “memory value”. Avelar affirms that there is an insistence, a persistence of memory beyond the dual logic I mentioned earlier. “What cannot be replaced what lingers on as a residue of memory is precisely the allegorically charged ruin…that of memory value, a paradoxical kind of value, to be sure, because what is most proper to it is to resist any exchange. It is due to that insistence of memory, of the survival of the past as a ruin in the present that mourning displays a necessarily allegorical structure” (5).(2) It is this definition of allegory as an exercise of memory that Avelar employs as his theoretical framework to examine postdictatorial texts. In Avelar’s book, the work of mourning is proposed as a mechanism of resistance against the commodification of Latin American society that neo-liberal models imposed. He juxtaposes a passive forgetting inherent to this society dominated by merchandise and money and an active forgetting that, according to him, corresponds to mourning.

How is restitution possible or conceivable when that which is to be restituted belongs in the order of affect? (ix). With this question Idelber Avelar begins his text The Untimely Present which studies postdictatorial fiction in Latin America and the task of mourning. The text by Avelar attempts to think the inherent value of memory. According to him, memory cannot be reduced to either its use value or its exchange value. Memory has intrinsic value that he names “memory value”. Avelar affirms that there is an insistence, a persistence of memory beyond the dual logic I mentioned earlier. “What cannot be replaced what lingers on as a residue of memory is precisely the allegorically charged ruin…that of memory value, a paradoxical kind of value, to be sure, because what is most proper to it is to resist any exchange. It is due to that insistence of memory, of the survival of the past as a ruin in the present that mourning displays a necessarily allegorical structure” (5).(2) It is this definition of allegory as an exercise of memory that Avelar employs as his theoretical framework to examine postdictatorial texts. In Avelar’s book, the work of mourning is proposed as a mechanism of resistance against the commodification of Latin American society that neo-liberal models imposed. He juxtaposes a passive forgetting inherent to this society dominated by merchandise and money and an active forgetting that, according to him, corresponds to mourning.

Avelar’s primary concern is to discover the value of memory and the role that it plays in postdictatorial literature in Latin America. In his theoretical framework there is a strong condemnation of all things related to money, commodity, or market precisely because these are associated with the dictatorships and their legacies. Avelar writes:

growing commodification negates memory because new commodities always replace previous commodities, send them to the dustbin of history. The free market established by the Latin American dictatorships must, therefore, impose forgetting not only because it needs to erase the reminiscence of its barbaric origins but also because it is proper to the market to live in a perpetual present. The erasure of the past as past is the cornerstone of all commodification, even when the past becomes yet another commodity for sale in the present. (2)

This reservation with what money represents places money in a binary relationship with memory. Money appears antithetical to memory and its value because it does not allow for the work of mourning to occur. It is precisely for this reason that Avelar is not satisfied with reducing memory merely to its use value or its exchange value. He contends that there must be memory value that supersedes material things such as money or market. Just like “what is most proper to mourning is to resist its own accomplishment, to oppose its own conclusion” (4), what is most proper to memory value is to resist exchange (5). This memory value represents a resistance to the imperative of the dictatorships both during and after their years of rule to erase the past.

The value of memory, for Avelar, lies in its ability to rescue the past from its ruins. Because it is inextricably linked to a temporality, even if it is in the present that postdictatorial texts are “dealing” with the ruins of the past, the value of memory very much resembles allegory’s relationship with time. Using Benjamin’s thesis, Avelar contends that allegory always bears the “marks of its time of production” (4). It is for this reason, therefore, that “the metaphor of memory-as-theater, as opposed to memory-as-instrument, makes the remembered image condense in itself, as a scene, the entire failure of the past, as an emblem rescued out of oblivion” (10). The value of memory lies in its ability to rescue, preserve, and mourn the past as well as represent the crisis of the present.

Perhaps the most important problem with Avelar’s conception of memory is that he conceives it beyond the monetary and market sphere and, therefore, as a transcendental space that escapes the logic of justice. This has as the most important consequence that he is incapable of translating memory into any real political or legal battle. The impossibility of translating the loss brought about by historical violence into the economic terms of injury and restitution converts memory into a sacred space that exists beyond representation.(3) Nietzsche, in one of his best writings about the sacralization of the past and of memory in the Genealogy of Morals had warned us about the relationship that exists between the mnemonic mechanisms and the economy of injury, guilt and punishment:

Throughout the greater part of human history punishment was not imposed because one held the wrong-doer responsible for his deed, thus not on the presupposition that only the guilty one should be punished: rather, as parents still punish their children, from anger at some harm or injury, vented on the one who caused it—but this anger is held in check and modified by the idea that every injury has its equivalent and can actually be paid back, even if only through the pain of the culprit. And whence did this primeval, deeply rooted, perhaps by now ineradicable idea draw its power—this idea of an equivalence between injury and pain? I have already divulged it: in the contractual relationship between creditor and debtor, which is as old as the idea of “legal subjects” and in turn points back to the fundamental forms of buying, selling, barter, trade, and traffic. (63)

Memory and Laughter

Rubén Ríos in his book La raza cómica proposes a work of memory that is much more hybrid and much less solemn and pure. His conception of memory seems much more in line with the books that I study in this essay. Furthermore, Ríos focuses his reflection on the changes that the practice of memory suffers, on the condition of inheriting in postcolonial societies and in marginal cultures. He summarizes his manner of conceiving the politics of memory in the following fragment: “una memoria del futuro como posibilidad, no del pasado como condición” (115). One of the first important lessons Ríos’ book teaches us is a different notion of a return, a different relationship with the past. He presents the book as a return to certain categories that have in some ways been “transcended” by present critical debate:

la identidad, la nación, el padre, la raza, la colonia, el trauma. Mi interés ha sido que el regreso a estas categorías tan conocidas desestabilice de forma productiva los modos tradicionales de acercarse a lo cultural como a lo político. Hay que regresar a ellas, pero no para reificarlas, ni para que vuelvan a ser “respetables”, sino con toda la intención de poner de manifiesto el vórtice poderoso de su imposibilidad. (9)

A return to the past, inheriting it, does not mean creating an artificial continuity with a “before” that is reified, nor does it mean the ossification of that previous epoch with commemoration rituals that consecrate documents and monuments. A return to the past means to assume its radical restlessness, its unruly discomfort.

This return will require breaking away from the various fictions about origin whether we understand it as the cause of a trauma, as the crisis of the present, or as a source of meaning. The origin has to be converted into yet another moment in history, another narrative, devoid of any privilege and mysticism tied to a foundational moment: “Hay que defenderse de  toda hermenéutica del origen del síntoma... De lo que se trata es de escuchar los ruidos del trauma [del origen], los conatos de cuentos deshilvanados que intentan articular aquí y allá los retazos de verdad” ( 28) . This listening to the noise of the trauma, to the articulation of the dissonant narratives that make them up, requires a different way of commemorating, a different way of mourning and inheriting.

toda hermenéutica del origen del síntoma... De lo que se trata es de escuchar los ruidos del trauma [del origen], los conatos de cuentos deshilvanados que intentan articular aquí y allá los retazos de verdad” ( 28) . This listening to the noise of the trauma, to the articulation of the dissonant narratives that make them up, requires a different way of commemorating, a different way of mourning and inheriting.

The chapter in Ríos’ book that is of most interest to my study is the one titled “Velorio” where he analyzes the painting also called El velorio by the Puerto Rican painter Francisco Oller. The painting was done in 1893 to commemorate the fourth centennial of the discovery of the island. Ríos describes the painting like this:

La obra pinta un baquiné, un velorio de infante, sin pena ni llanto, porque se entiende que el niño de cuerpo presente es un ángel sin alas que murió sin pecar. El baquiné era un ritual bastante común en el campesinado, de origen supuestamente extranjero, aparentemente tortoleña su procedencia, que, ante la solemnidad del velorio católico español, se le aparece al buen burgués criollo como una profanación del cadáver. (45)

It is the image of this mourning “sin penas ni lágrimas” “without sorrows or tears”, this bastardly form, against solemnity, which places us before a cadaver, before a ghost, that will help to guide our reading in the rest of this essay. The ambivalence of this mourning without liturgy, of this wake where mourning and a party get mixed, will help us think about the different ways that inheritance is articulated in the texts that will be studied below.

Memory, Mourning and Humor in the Latin American Literary Tradition

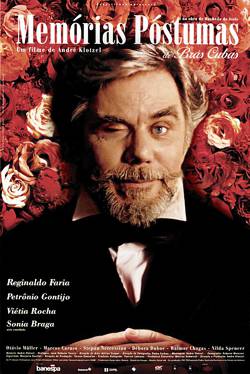

Machado de Assis’ Memorias postumas can be read as a text-testament that also reflects on the paradoxes of an inheritance. At the end of the book, in his chapter of negatives, “Das negativas”, the narrator declares: “não tive filhos, não transmiti a nenhuma criatura o legado da nossa miséria”(4) (235). This paradoxical testament ends with a sum of all the frustrations of the posthumous narrator’s life and it eliminates the possibility of the continuity of this catastrophic legacy. This text-memoir also can and ought to be read as a text that reflects on how one can inherit a form (the 19th century novel) from the other world, in the margins.(5) The literature that is written in the periphery has the form of mourning and parody. All texts that are written in the periphery are posthumous because they inherit a dead form, a decadent form that is inadequate in its immediate environs. One can inherit a genre only by parodying it and telling about its death. The writers that live in the periphery, that live in the beyond (as is the case of Machado de Assis’ narrator), can only inherit the remains of the 19th century novel, its ruins. This legacy, both mournful and hilarious, allows us to reflect about the coexistence of mourning and humor. The only way of giving new life to specters is by laughing at and with them. I am interested in tracing a Latin American tradition of reading that uncovers a different form of dealing with specters not based on Hamlet’s model(6) but on writers that wrote in conditions that were marginal and peripherical: Machado de Assis, Guillermo Cabrera Infante and Claudia Hernández.

inheritance. At the end of the book, in his chapter of negatives, “Das negativas”, the narrator declares: “não tive filhos, não transmiti a nenhuma criatura o legado da nossa miséria”(4) (235). This paradoxical testament ends with a sum of all the frustrations of the posthumous narrator’s life and it eliminates the possibility of the continuity of this catastrophic legacy. This text-memoir also can and ought to be read as a text that reflects on how one can inherit a form (the 19th century novel) from the other world, in the margins.(5) The literature that is written in the periphery has the form of mourning and parody. All texts that are written in the periphery are posthumous because they inherit a dead form, a decadent form that is inadequate in its immediate environs. One can inherit a genre only by parodying it and telling about its death. The writers that live in the periphery, that live in the beyond (as is the case of Machado de Assis’ narrator), can only inherit the remains of the 19th century novel, its ruins. This legacy, both mournful and hilarious, allows us to reflect about the coexistence of mourning and humor. The only way of giving new life to specters is by laughing at and with them. I am interested in tracing a Latin American tradition of reading that uncovers a different form of dealing with specters not based on Hamlet’s model(6) but on writers that wrote in conditions that were marginal and peripherical: Machado de Assis, Guillermo Cabrera Infante and Claudia Hernández.

Another book that excellently demonstrates the singular dialectic that is seen in Latin American literature between mourning and humor is Tres tristes tigres. This book is undoubtedly one of the most humorous reflections about the act of remembering. Cabrera Infante is simultaneously playing with and questioning the act of remembering by constantly breaking it apart and bringing it closer and closer to the forbidden land of hilarity. How better to describe the seven versions of the death of Trotsky? Though the subject of the reflections is a solemn one, the betrayal and assassination of an important historical figure of the twentieth century, the written versions are hysterical. The telling of history is pushed to a limit that historians will never want to approach. Each version, as Cabrera Infante imagines his fellow writers would have written it, is full of idiosyncrasies that have more in common with the supposed authors than with the historical figure of Trotsky. This very obvious limitation of a historical account is taken to such an extreme that historical accounts appear to have much more in common with our retelling of dreams and with our nostalgic remembrances of lived experiences than we would normally want to admit. How to differentiate these versions, for instance, from the psychoanalytical sessions of a troubled woman that Cabrera Infante  intersperses throughout his narrative? How to reconcile this woman’s reflection, “lo cierto es, doctor, que yo no sé si me pasó a mí o si le pasó a mi amiguita o si lo inventé yo misma”? (472) with our desire to legitimate psychoanalysis and believe in the power of uncovering our past? By imbuing his entire novel with humor, this nostalgic reconstruction of nightlife in La Habana is able to dismantle all our preconceived notions of what it means to remember.

intersperses throughout his narrative? How to reconcile this woman’s reflection, “lo cierto es, doctor, que yo no sé si me pasó a mí o si le pasó a mi amiguita o si lo inventé yo misma”? (472) with our desire to legitimate psychoanalysis and believe in the power of uncovering our past? By imbuing his entire novel with humor, this nostalgic reconstruction of nightlife in La Habana is able to dismantle all our preconceived notions of what it means to remember.

Cabrera Infante explicitly tackles the problem of remembering through his character Silvestre. After Cué has accused Silvestre that he has never truly been in love, Silvestre embarks on a long and very important reflection about what it means to remember:

Esta imagen me asalta ahora con violencia, casi sin provocación y pienso que mejor que la memoria involuntaria para atrapar el tiempo perdido, es la memoria violenta, incoercible, que no necesita ni madelenitas en el té ni fragancias del pasado ni un tropezón idéntico a sí mismo, sino que tiene abrupta, alevosa y nocturna y nos fractura la ventana del presente con un recuerdo ladrón. No deja de ser singular que este recuerdo dé vértigo: esa sensación de caída inminente, ese viaje brusco, inseguro, esa aproximación de dos planos por la posible caída violenta (los planos reales por una caída física, vertical y el plano de la realidad y el del recuerdo por la horizontal caída imaginaria) permite saber que el tiempo, como el espacio, tiene también su ley de gravedad. Quiero casar a Proust con Isaac Newton. (322-23)

This law about the “gravity of memory” is linked in Cabrera Infante’s text with the violence of history. This violent and incoercible memory, as Cabrera Infante characterizes it, will be a privileged path to the past for both authors, a path to times past. We have already seen in this essay that any attempt to recover what is gone, what is lost or dead, requires work, the work of mourning; and we also know that this work is accompanied by another specter, the “buzzing” bantering and teasing tone of irony.

Using the notion of memory and irony that I propose above, I will now focus on the short stories by Claudia Hernández that appear in the book De fronteras.(7) Claudia Hernández (b. 1975) is one of the most important postwar Salvadoran writers today. Though she is a part of a generation of writers who grew up during the Salvadoran Civil War (1979-1992), her stories do not address the war or its effects directly. This eschewing away from politics, however, does not mean that the war and its aftermath are not alluded to in her fantastical and grotesque stories. As Misha Kokotovic writes in his essay “Telling Evasions: Postwar El Salvador in the Short Fiction of Claudia Hernández”:

that appear in the book De fronteras.(7) Claudia Hernández (b. 1975) is one of the most important postwar Salvadoran writers today. Though she is a part of a generation of writers who grew up during the Salvadoran Civil War (1979-1992), her stories do not address the war or its effects directly. This eschewing away from politics, however, does not mean that the war and its aftermath are not alluded to in her fantastical and grotesque stories. As Misha Kokotovic writes in his essay “Telling Evasions: Postwar El Salvador in the Short Fiction of Claudia Hernández”:

Hernández’s stories stand out from much postwar Central American fiction because they do not refer to the war and its consequences overtly, in more or less realist fashion, but rather allude to the conflict’s enduring effects in the troubled and paradoxically violent peace of the 1990s obliquely, by subtly calling attention to their own silence on the subject. By making such evasion visible, the stories in Mediodía de frontera(8) expose the unacknowledged costs of El Salvador’s pacification and call into question the project of national reconciliation without accountability for the crimes committed during the war (54-55).

This “calling attention to their own silence on the subject” that Kokotovic mentions is of great signficance given that the abject violence that many of the stories represent do not come out of a vacuum and are a direct legacy of the brutal conflict that left millions displaced, tens of thousands dead, thousands wounded and an entire nation broken.(9) Hernández’ approach to this violent past and to the memory of the war is unique. Other contemporary Salvadoran authors such as Horacio Castellanos Moya have written about the war and its aftermath in a similarly sarcastic and parodic tone but none have combined this sarcasm and parody with mourning. Hernández’ inheritance of this violent legacy and the aftermath of a civil war falls in line closely with texts that I have previously analyzed in this essay.

In the stories I analyze from De fronteras, Hernández subverts the task of mourning via the irony, the absurd and the sarcasm that she employs. The task of mourning is perhaps the principal affective and rhetorical mechanism through which one attempts to confront a traumatic past, such as one left behind by a civil war. All the stories that I focus on recount the metamorphosis of mourning into something else, and it is through this transformation and subversion that these texts propose a new politics and rhetoric to confront the unbearable weight of this traumatic past. I will analyze, then, the ways in which mourning is subverted in these stories.

The first rhetorical mechanism that Hernández employs to subvert mourning I will call the literalization of mourning which pretends to attain at a literal level what mourning proposes at a more metaphorical and symbolic level: the total restitution of a loss. This restitution is achieved by two figurative processes in her stories: the protagonist attempts to mimic, to occupy the place of the lost cadaver. This mechanism is evident in the stories “Carretera sin buey” and “Melisa: juegos 1 al 5”. Hernández appears to propose that in order to get close to the dead we have to be like them, we have to become the dead. The second way in which Hernández’ stories propose a total restitution of the lost object is through a reincorporation of the cadaver into the world of the living as seen in the story “Abuelo”. In order to replace the emotional, rhetorical, and political loss that the death of a loved one leaves behind, one disinters the cadaver and distributes its parts among all the loved ones mourning it. The third, fourth and fifth mechanisms propose an ethics. The first one of these ethical devices could be defined as an ethics of hospitality. The story “Hechos de un buen ciudadano (Parte I)”, the exemplary text in this group, begins stating: “Había un cadáver cuando llegué. En la cocina. De mujer. Lacerado” (17). How can one accept in one’s own house that radical other, the cadaver of someone we do not know? How are we able to put this cadaver in circulation so that it can function in the economy (affective and material) of the living? This ethics of hospitality(10) goes to the absurd extreme of offering as a gift, as food, this cadaver of a stranger to the homeless, to those whom nobody has given any hospitality. The fourth rhetorical mechanism that Claudia Hernández employs to subvert the traditional notion of mourning is to strip the loss of its tragic and traumatic character, as seen in the story “Mediodía de frontera”. In these stories, Hernández proposes a postmortem ethics: in her universe, it is the dead who care for the living. Death, in order to look at life in the face, puts its best face forward, it makes itself up even if it is at the tragic cost of self mutilation. The most important thing, as we will see shortly, is to not die with your tongue sticking out. In the fifth one of these rhetorical devices used, irony, sarcasm and the subversion of mourning reach their maximum climax. “Manual del hijo muerto” is, as its title suggests, an instruction manual about how to mend, to repair and put together again the pieces of a missing child’s dismembered cadaver. This last mechanism can be described as an ethics that attempts to anesthetisize. Consumer society has a solution for everything and if one follows painstakingly the instructions manual which tells us how to put back together the dead child, the process of mourning will be stripped of its pathos and one will be able to do something productive with the loss. What I attempt to describe in this essay is Hernández’ apparent goal in this collection of stories: the grotesque presentation and radical metamorphosis of mourning . For the sake of brevity, I will analyze three stories from this collection: “Melissa: juegos 1 al 5”, “Carretera sin buey”, “ Mediodía de frontera”.

The first rhetorical mechanism that Hernández employs to subvert mourning I will call the literalization of mourning which pretends to attain at a literal level what mourning proposes at a more metaphorical and symbolic level: the total restitution of a loss. This restitution is achieved by two figurative processes in her stories: the protagonist attempts to mimic, to occupy the place of the lost cadaver. This mechanism is evident in the stories “Carretera sin buey” and “Melisa: juegos 1 al 5”. Hernández appears to propose that in order to get close to the dead we have to be like them, we have to become the dead. The second way in which Hernández’ stories propose a total restitution of the lost object is through a reincorporation of the cadaver into the world of the living as seen in the story “Abuelo”. In order to replace the emotional, rhetorical, and political loss that the death of a loved one leaves behind, one disinters the cadaver and distributes its parts among all the loved ones mourning it. The third, fourth and fifth mechanisms propose an ethics. The first one of these ethical devices could be defined as an ethics of hospitality. The story “Hechos de un buen ciudadano (Parte I)”, the exemplary text in this group, begins stating: “Había un cadáver cuando llegué. En la cocina. De mujer. Lacerado” (17). How can one accept in one’s own house that radical other, the cadaver of someone we do not know? How are we able to put this cadaver in circulation so that it can function in the economy (affective and material) of the living? This ethics of hospitality(10) goes to the absurd extreme of offering as a gift, as food, this cadaver of a stranger to the homeless, to those whom nobody has given any hospitality. The fourth rhetorical mechanism that Claudia Hernández employs to subvert the traditional notion of mourning is to strip the loss of its tragic and traumatic character, as seen in the story “Mediodía de frontera”. In these stories, Hernández proposes a postmortem ethics: in her universe, it is the dead who care for the living. Death, in order to look at life in the face, puts its best face forward, it makes itself up even if it is at the tragic cost of self mutilation. The most important thing, as we will see shortly, is to not die with your tongue sticking out. In the fifth one of these rhetorical devices used, irony, sarcasm and the subversion of mourning reach their maximum climax. “Manual del hijo muerto” is, as its title suggests, an instruction manual about how to mend, to repair and put together again the pieces of a missing child’s dismembered cadaver. This last mechanism can be described as an ethics that attempts to anesthetisize. Consumer society has a solution for everything and if one follows painstakingly the instructions manual which tells us how to put back together the dead child, the process of mourning will be stripped of its pathos and one will be able to do something productive with the loss. What I attempt to describe in this essay is Hernández’ apparent goal in this collection of stories: the grotesque presentation and radical metamorphosis of mourning . For the sake of brevity, I will analyze three stories from this collection: “Melissa: juegos 1 al 5”, “Carretera sin buey”, “ Mediodía de frontera”.

The notion of mourning that Hernández proposes in her stories, particularly in “Melissa: juegos 1 al 5” and “Carretera sin buey”(11) is disturbing because it makes literal a necessity that is symbolic. In the first story, a little girl whose mother has taken her to pick up her grandmother’s cadaver reconstructs various scenes of dead people in each one of the five games that she plays and that the story describes. In the first one, the little girl is laying down on the garden with her little hands crossed on her chest and covered with flowers. In the second one, the girl pretends to be a cat which has been hit and dragged by a car, and she places green and purple leaves around herself to simulate the entrails. In the third game we see the same little girl, throwing herself on her father’s legs, with open eyes, a stretched neck, and a lost gaze while she explains to him that she is a dead dove. In the fourth game, we find ourselves in the little girl’s room where she pretends to be in charge of a morgue and has all her dolls catalogued: some are buried, others are waiting to be tended to, and others are ready to be taken away by their loved ones. Finally, in the fifth game, we see little clay animal and food figurines. In all these games we see how the symbolic process of mourning is taken by the little girl to a literal sphere, to a space that borders with monstrosity and perversion. In a typical mourning process, the work of mourning consists of a process of acceptance of a loss. What the subject seeks in the work of mourning is the acceptance of the nonexistence of something, the acceptance of an absence. The work of mourning has two faces: on the one hand, it is the acceptance of a loss and on the other, it is the recognition that the lost object is invaluable, irreplaceable, untranslatable and cannot be exchanged for or substituted with another object. The little girl from the story, however, is incapable of accomplishing this process and of understanding the finality of death. She does not accept the loss since by simulating death and by pretending to be the dead one, she does not accept the absence of the grandmother. She also does not understand the irreplaceable value of the loss since she is constantly reinventing the lost object.

The story “Carretera sin buey” presents another example of a protagonist who wants to occupy the space of the dead. In this case, however, the dead being is an ox and the survivor is a man. The story is narrated with a first person plural voice that we never get to know. We only know that this ‘we’ is traveling in a car on a road and in the distance sees a lanky but beautiful ox with its gaze turned to eternity. When this collective ‘we’ slows down and find themselves close to the ox they realize that it is actually a man and cannot find the right words to apologize and get away as fast as possible because, had they known that it was a man and not an animal, they would never have stopped. The man who is thrilled to be taken for an ox explains to them the reason for his current state. He tells them that he ran over the ox and killed it and now cannot forget it. Unable to accomplish the process of mourning, he returns to the road in order to simulate being the ox and to take its place. Standing on the road, he does everything he can to look like the ox that he killed and cannot forget. He suffers every day because every time he asks those who pass on the road, they answer that they see a man on the side of the road. Each one of these responses reminds him of his incapacity to “poder reponer al buey consigo mismo” (24). After listening to this story, the passengers find themselves moved by his predicament, and have pity on him and decide to give him a final and definite piece of advice: in order to look like an ox he has to castrate himself. The man, very grateful, takes their advice and accepts their help with the castration.

In this case, however, the dead being is an ox and the survivor is a man. The story is narrated with a first person plural voice that we never get to know. We only know that this ‘we’ is traveling in a car on a road and in the distance sees a lanky but beautiful ox with its gaze turned to eternity. When this collective ‘we’ slows down and find themselves close to the ox they realize that it is actually a man and cannot find the right words to apologize and get away as fast as possible because, had they known that it was a man and not an animal, they would never have stopped. The man who is thrilled to be taken for an ox explains to them the reason for his current state. He tells them that he ran over the ox and killed it and now cannot forget it. Unable to accomplish the process of mourning, he returns to the road in order to simulate being the ox and to take its place. Standing on the road, he does everything he can to look like the ox that he killed and cannot forget. He suffers every day because every time he asks those who pass on the road, they answer that they see a man on the side of the road. Each one of these responses reminds him of his incapacity to “poder reponer al buey consigo mismo” (24). After listening to this story, the passengers find themselves moved by his predicament, and have pity on him and decide to give him a final and definite piece of advice: in order to look like an ox he has to castrate himself. The man, very grateful, takes their advice and accepts their help with the castration.

The inability to observe the process of mourning is taken in this story to an absurd level. The narrator states that “Lo había intentado más de diez veces. Había levantado su duelo y regresado a casa; pero, a diario cuando pasaba por ese camino, sentía la falta del buey. Miraba el vacío del animal y no podía continuar tranquilo aunque él mismo se había encargado de hacerle compañía y hablarle mientras estuvo en el trance de la muerte” (24). In the traditional process of mourning we confront the haunting of a past that gets diluted, a traumatic past that returns and gets out of joint(12) with the linear and orderly time of the living. In Hernández’ stories it is the living, those who live on this side, who take the place of those who left. All her stories describe the metamorphosis of the symbolic economy that mourning entails. The present is dressed with the past, the living replaces the dead, the man mutilates and deforms his body in order to simulate, to perfection, the silhouette of the animal that died because of him. The reinvention that mourning accomplishes on the concept of labor, an accumulation of losses instead of earnings, an acceptance of a loss of a valuable object instead of a subtitution of it, is distorted in these stories. These stories propose a pervese fantasy of a mourning that only accepts total restitutions. If we want to recover that ‘someone’ lost, let’s occupy his place, let’s die in its place. The only way to communicate with the dead and with death seems to be by usurping its place. We have to inhabit the threshold that separates us from the irreparable and lost world where the dead of history live. Claudia Hernández’ short stories grant a voice, in a perverted and inverted manner, to the fantasy-prophecy in Marx’s XVIII Brumaire. Instead of the dead burying the dead, the living will bury the living.

In the shorty story “Mediodía de fronteras” we can see the fourth rhetorical device that subverts mourning that I described above. This story could have as a subtitle “the adventures of a tongue” or “how hunger overtakes any notion of mourning”. It narrates the conversation between a woman who has just cut off her tongue and a hungry dog in a border area that the story does not name. How they communicate is unclear. We have to expect a reflection about the failure or the impotence to grant meaning to the world, to uncover the taste and the knowledge of life of any story that tells us of a self-mutilation of the tongue.(13) The mutilated tongue in this story has not lost its flavor, the protagonist gives it to the hungry dog and the narrator says, “Sabe bien la lengua. Muy bien. El primer trozo, el segundo. Toda” (103). It also does not lack knowledge. The understanding between the protagonist and the dog is almost perfect, before and after the words. “‘Comprendo’, dice el perro y en realidad lo hace” (102), the narrator tells us. But what does the dog understand? What is the understanding between the dog and the protagonist based on when it is born before language and survives it even after the capacity to speak (the woman no longer has a tongue, afterall) is gone? The dog understands that the protagonist cut off her tongue because she wants to hang herself and “los ahorcados no se ven mal porque cuelguen del techo, sino porque la lengua cuelga de ellos. La lengua es lo que provoca horror, la lengua es lo que provoca lástima...Y ella no quiere horrorizar a nadie. Solo quiere ahorcarse” (103). The brutal irony, the absurdity and the sarcasm in this story proposes a postmortem ethics where the cadavers want to save us (the living), even if it means their own mutilation, from the horror and the trauma we might feel with a possible future encounter with them. The living (the woman in this story) continue to prepare the theater of death, they occupy the place of the dead, in this case, the woman makes preparations for her own death so that the encounter with her own cadaver can be the least traumatic possible. In his book Specters of Marx, Derrida writes that “Mourning always follows a trauma” (97). But what happens if we have a process of mourning without a before, without a traumatic past that mourning presupposes?:

Llora el perro y permanece a su lado aunque ella ya no lo sepa. Se queda...No se mueve pese a que entran muchos. La gente lo deja quedarse porque creen que es su mascota...La acompaña hasta que llegan los encargados de descolgarla y se la llevan… No contesta cuando le preguntan qué sucedio. No lo explica, sólo mira cómo se la llevan en un camión. Regresa al baño a lamer un poco de sangre antes de que bloqueen la puerta con cintas amarrillas o antes de que limpien. Todavía tiene un poco de hambre (103).

The dog watches over the cadaver of the woman he met just a few minutes before. He stays by her side, in the manner that ‘only man’s best friend’ can. He does not abandon her until he makes sure that her body has been taken away and will be given a proper burial. Claudia Hernández seems to ask us: How can we remember someone that we do not know and with whom we have nothing in common? How do we safeguard the memory of someone whose past we don’t know? How to remember and commemorate in a country that has not yet fully accounted for (numerically and metaphorically) its dead? How to do the work of mourning in a country that still needs the necessary mechanisms and institutions to confront the traumatic past of the war?

The absurdity and brutal irony of the story “Mediodía de fronteras”, the coldness(14) with which it is narrated does not take away its profound humanity, in fact, it does quite the contrary. We cannot forget that despite the fact that the woman and the dog do not share a common past, they share the gift of language(15) and they shared her tongue. The woman gave her tongue as a gift to the dog, she fed him with the organ with which she gave taste and knowledge (language) to her life. At the end of the story, the dog licks the blood of his anonymous friend. With his tongue? With hers? His stomach growls. His friend’s tongue lives inside him now, in his entrails, that organ which gave her the ability to savor life, figuratively and literally. His hunger and her blood will be forms of remembrance. Claudia Hernández’ stories narrate, as I said earlier, the metamorphosis of mourning. They present a disfigured, grotesque and absurd mourning. But despite having these characteristics, mourning is not stripped of its utmost humanity.

Notes

1. There are at least two other books that require at least brief commentary in this essay: State Repression and the Labors of Memory by Elizabeth JelinandPolíticas y estéticas de la memoriaedited by Nelly Richard. I do not include these books in this essay for two reasons: a detailed discussion of these books would require a very long detour away from my argument and secondly, the reservations that I have about Avelar’s text can also be applied to these two texts.

2. Avelar follows Walter Benjamin’s relationship between mourning and allegory. In Benjamin, allegory recovers its sacred value. Allegory is not only a translation of a literal meaning, allegory implies the salvation of a meaning marked by its own death. Allegory attempts to save a meaning whose very own destruction is imminent. It is only as a corpse, according to Benjamin, that one can enter the homeland of allegory. Allegory, therefore, is a trope of memory. Allegory remembers the loss of meaning.

3. Noga Tarnopolsky’s article in The New Yorker “The Family that Disappeared” tells us the story of Daniel Tarnopolsky, a youth of 16 years who in 1976 lost his entire family: father, mother, brother and sister. They were among the victims of the disappearances, tortures and assassinations committed by the Argentine military junta of those years. Daniel, in one of the most dramatic moments in the article says in a legal suit he placed against the Argentine government, “the only thing that most lasts is memory—national memory—and, if I win my lawsuit memory wins.” John Borneman in an essay entitled “On Money and the Memory of Loss” asks, what type of compensation can money give memory? Borneman affirms that: “money cannot transvalue memory but it can transvalue loss” (8) and that “money…does not rely on access to memory in order to relate to loss. It speaks to loss directly.” (9) I ask, in what way does money address and redress Daniel’s loss? What type of victory does money grant memory? For Daniel it seems that to win his lawsuit means to win his right (and that of his compatriots) to remember. One can also look at this victory and read it in a different way: to remember and to construct a national memory is not a spontaneous natural action but rather an action that is immersed in power and legal struggles in which money has a central role. These cases demonstrate the importance of memory beyond the sacred space which Avelar seems to relegate it to in his book.

4. I did not have kids, I did not transmit to anybody the legacy of our misery”. Unless otherwise noted, the translations are my own.

5. For a more thorough study of this text see Roberto Schwarz’ book A Master on the Periphery of Capitalism: Machado de Assis.

6. Here I am referring to Jacques Derrida’s book Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New Internationalwhere Derrida makes Hamlet his literary model to think about the relationship between ghosts and the task of mourning.

7. Though there are still few scholarly articles written about her work, for further reading about Hernández see Linda Craft’s article “Viajes fantásticos: Cuentos de [in]migración e imaginación de Claudia Hernández” and Misha Kokotovic’s Telling Evasions: Postwar El Salvador in the Short Fiction of Claudia Hernández.

8. The collection of stories was originally published in El Salvador under the Dirección de Publicaciones e Impresos in 2002 under the title Mediodía de fronteras but I am using the second edition published in 2007 in Guatemala which appeared under the title De fronteras.

9. For futher study of the conflict and its aftermath, consult the United Nation’s truth commission report De la locura a la esperanza: La guerra de 12 años en El Salvador.

10. For a notion of hospitality understood as the welcoming of a stranger or foreigner with whom we do not have any family ties see Derrida’s Of Hospitality (Cultural Memory in the Present).

11. For a reading of this story as an allegory of the construction of identity see Beatriz Cortez’ book Estética del cinismo. Pasión y desencanto en la literatura centroamericana de posguerra.

12. This phrase comes from Derrida’s book Specters of Marx who in turn borrrows it from Shakespeare.

13. Another example of the mutilation of a tongue in Latin American literature you can see the story “Lengua” by Horacio Quiroga and for an analysis of the story, consult Julio Ramos’ “El don de la lengua” included in the book Paradojas de la letra.

14. The obvious allusion to Virgilio Piñeras Cuentos fríos is evident throughout this collection of short stories. The absurdity and irony is reminiscent of Piñera.

15. In Spanish, the word for tongue and for language is the same: ‘lengua’. In this case, the gift of the tongue is literally and figuratively what I mean: they share a common language and they shared her tongue.

Bibliography

Avelar, Idelber. The Untimely Present: Postdictatorial Latin American Fiction and the Task of Mourning. Durham: Duke UP, 1999. Print.

Borneman, John. "On Money and the Memory of Loss," in Restitution and Memory: Historical Remembrance and Material Restitution in Europe. Ed. Dan Diner and Gotthart Wunberg, New York: Berghahn Books, 2007. Print.

Cabrera Infante, Guillermo. Tres tristes tigres. Spain: Editorial Seix Barral, 1997. Print.

Cortez, Beatriz. Estética del cinismo: Pasión y desencanto en la literatura centroamericana de posguerra. Guatemala: F&G Editores, 2010. Print.

Craft, Linda J. “Viajes fantásticos: Cuentos de [in]migración e imaginación de Claudia Hernández.” Revista Iberoamericana 242 (2013): 181-194. Print.

Derrida, Jacques. Specters of Marx: The State of Debt, the Work of Mourning. New York: Routledge, 1994. Print.

Hernández, Claudia. De fronteras. Guatemala: Piedra Santa, 2007. Print.

Jelin, Elizabeth. State Repression and the Labors of Memory. Trans. Judy Rein and Marcial Godoy-Anativia. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 2003. Print.

Kokotovic, Misha. “Telling Evasions: Postwar El Salvador in the Short Fiction of Claudia

Hernández”. A Contracorriente, North America, 11, jan. 2014. Available at: <http://acontracorriente.chass.ncsu.edu/index.php/acontracorriente/article/view/767>. Accessed 22 Feb. 2014. Electronic.

Machado de Assis. Memórias póstumas de Brás Cubas. São Paulo, Brazil: O Globo/Klick

Editora, 1997. Print.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. On The Genealogy of Morals. Trans. and Ed. Walter Kaufmann and R.J. Hollingdale. New York: Vintage Books Edition, 1989. Print.

Richard, Nelly. ed. Políticas y estéticas de la memoria. Santiago: Cuarto Propio, 2000. Print.

Ríos Ávila, Rubén. La raza cómica. San Juan: Ediciones Callejón, 2002. Print.

Schwarz, Roberto. A master on the periphery of capitalism: Machado de Assis. Translated by

John Gledson. Durham: Duke UP, 2001. Print.

Tarnopolsky, Noga. “The family that disappeared,” The New Yorker, Nov. 15, 1999, pp. 48-57.

Print.

Umaña, Fernando. “Perdí la mitad de mi generación en la guerra”. El Faro. Periódico digital.

archivo.elfaro.net/secciones/el_agora/.../ElAgora1_20070115.asp. Accessed 15 December 2013. Electronic.