|

|

|

|

||

| La Azotea de Reina | El barco ebrio | Ecos y murmullos | La expresión americana | ||

| Hojas al viento | En la loma del ángel | La Ronda | La más verbosa | ||

| Álbum | Búsquedas | Índice | Portada de este número | Página principal | ||

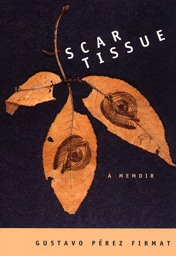

| Scar Tissue* Gustavo Pérez Firmat Los primeros poemas de Gustavo Pérez Firmat que recuerdo haber leído son los que recogió la  antología

Poesía cubana: la isla

entera, de Felipe Lázaro y Bladimir Zamora (Betania,

1995). En ellos uno reconoce los malabares lingüísticos,

las infinitas asociaciones en el diván de la escritura a que nos

ha acostumbrado. Pienso que su trabajo con el lenguaje está

atado, es indisociable, de la experiencia de la extranjería. No

se trata, sin embargo, de una extranjería circunscrita a una

orilla, a una lengua, sino más bien a lo orillero como lugar de

desafíos, de borrón y cuenta nueva, de nuevos borrones, y

otra vez de nuevas cuentas, y así ad infinitum. Al posicionarse en la

orilla, Pérez Firmat se coloca en el lugar maldecido por los

discursos revolucionarios, y, en general, por las identidades fuertes:

en la cerca, en el medio. Quizá a esto se deba la movilidad de

su escritura, el continuo desenfoque del equipaje, los

descarrilamientos de una mirada que parece tan fascinada como

horrorizada con cada salto. antología

Poesía cubana: la isla

entera, de Felipe Lázaro y Bladimir Zamora (Betania,

1995). En ellos uno reconoce los malabares lingüísticos,

las infinitas asociaciones en el diván de la escritura a que nos

ha acostumbrado. Pienso que su trabajo con el lenguaje está

atado, es indisociable, de la experiencia de la extranjería. No

se trata, sin embargo, de una extranjería circunscrita a una

orilla, a una lengua, sino más bien a lo orillero como lugar de

desafíos, de borrón y cuenta nueva, de nuevos borrones, y

otra vez de nuevas cuentas, y así ad infinitum. Al posicionarse en la

orilla, Pérez Firmat se coloca en el lugar maldecido por los

discursos revolucionarios, y, en general, por las identidades fuertes:

en la cerca, en el medio. Quizá a esto se deba la movilidad de

su escritura, el continuo desenfoque del equipaje, los

descarrilamientos de una mirada que parece tan fascinada como

horrorizada con cada salto.Los poemas de Scar Tissue apuntan al descalabramiento del cuerpo, al balbuceo del corte, a la herida; herida apalabrada en el gozo de contemplarse en el espejo-cenicero de la página; o, para decirlo con el título de uno de los poemas, se trata de la “meada sabrosa,” del derrame y el festejo con que entra el lenguaje a su bien ganado domingo de resurrección. Francisco Morán *Gustavo Pérez Firmat. Scar Tissue (Arizona: Bilingual Press / Editorial Bilingüe, 2005). ANASTOMOSIS: A PROLOGUE When my father died, embittered and penniless after more than forty years of fruitless exile, I told myself that he had left me one invaluable legacy: the determination not to be like him. Two months  later, the diagnosis of prostate cancer, a disease from

which he had also suffered, put me in my place, his place. later, the diagnosis of prostate cancer, a disease from

which he had also suffered, put me in my place, his place.It’s been almost a year since I underwent what is called a radical retropubic prostatectomy – a relatively safe but complicated procedure designed to remove the malignancy with the smallest number of side effects. During these months of slow and sudden changes, I have often thought about my father, about the intertwining of our distant lives, about the links between exile and cancer – both so much concerned with foreignness. If nothing else, illness gives us the gift of self-awareness, in Spanish, conciencia. The wrenching in our body promotes a special kind of clarity, the mind’s revenge for the humiliation inflicted by the disease and its treatment. Not someone who gets over things quickly, for several weeks after the surgery I was unable to do little more than keep myself going from meal to meal. But as fall crept in (the operation took place in September), I began to feel like myself again, began to reestablish connection with the person I had been before the surgery as well as with the people around me – my wife, my children and stepchildren, my students. The surgeons’ term for this is “anastomosis” – the joining of blood vessels ar organs that have been separated by surgery. The notebook I started during those months, a journal of recovery and reconnection, is also a work of anastomosis. Writing it, I found my way to a place I had never been and had never left. Chapel Hill, North Carolina, August 2003 Incision She calls it my badge of courage, the thin red line that plunges from my navel into my pubis. I cannot look at it without seeing myself on the operating table like a chicken about to be halved. I hear the chatter of the medical men, chefs of my entrails, as they lean over me, cleavers in hand, deciding where to cut, what to spare, how to put almost everything back. I’m afraid to make out their words, afraid of what they know about me. My Body Was a Temple for Aristides Falcón-Paradí  I

used to think my body was a temple, but that was before the instruments

of strangers sliced it open. Now I think of it as an archeological dig,

ar a used-car lot like the one my father used to run, or the produce

section in a Cuban bodega, its wooden bins stuffed with overripe

tomatoes and pasty fruit. I

used to think my body was a temple, but that was before the instruments

of strangers sliced it open. Now I think of it as an archeological dig,

ar a used-car lot like the one my father used to run, or the produce

section in a Cuban bodega, its wooden bins stuffed with overripe

tomatoes and pasty fruit.Probably as many people have ever seen me naked as saw me that day with a mask over my face, IVs sprouting from my arms like tendrils, and my belly a study in scarlet. Did they find anything to admire inside me? A meandering vein? The delicately contoured lymph nodes? My ruddy, if lumpy, prostate? Or did they sift through my entrails with the mechanical care of the bodeguero discarding bruised limes? I would have liked my organs to impress them, would have wanted to hear them oohing over my bladder, ahing over my liver. But in the post-operative stupor all I hear is the tinkling of metal instruments and the subdued conversation of men and women going about their daily business, which on this particular Monday afternoon happens to be me. Cut My first outing after the surgery is to the barber. For years I’ve been having my hair styled at unisex salons where young gay men and less-than-young straight women reign supreme. Now I want as little fuss as possible. Tucked away between a pool hall and a Chinese tailor, Mr. Clark’s barbershop is nothing if not unfussy. The only furnishings are a sofa, a coat rack, an old-fashioned cash register that rings when it opens, and two barber chairs, only one of which gets any use. On the walls: a 30-year-old diploma from a barber college and a poster with the University of North Carolina basketball schedule. You get what you pay your $12 for: a plain haircut with clippers, a thin strip of tissue around your neck, and talcum powder. No shampoo, no massage, no mousse. No brightly colored aprons or aromatic candles. No Glamour and no glamour. In and out in fifteen minutes. Painless. Meada sabrosa for Wiíly Luis In Spanish it’s called mear, to pee. But “pee” is such a little sound – pee-wee, peanut, picayune, pipí  – that it doesn’t measure up, doesn’t da justice

to the cascading fluency of the act. – that it doesn’t measure up, doesn’t da justice

to the cascading fluency of the act.Mear: For the first two weeks, a plastic tube did it for me. Then it began again. At first it was only pitiful petty peeing, drip and dribble and dry. Then, gradually, peeing rose to mear, a verb with the sea – el mar – inside it. I felt thirty years old again. And then five. And then fifteen. Every morning I filled my bladder, suddenly a fountain of youth, just to see the stream – el chorro – gushing from me. I had forgotten how well a long, leisurely piss – una meada sabrosa – can make you feel, how it can erase loss and exile and aging. A medical man once told me: When you hit fifty, you’11 have to choose between pissing and screwing. At the time it didn’t seem like much of a choice. Now I know better. Still Life for Rafael Rojas The exile and the immigrant go through life at different speeds. The immigrant is in a rush about everything – in a rush to get a job, learn the language, set down roots, become a citizen. He lives in the fast lane and if he arrives as an adult, he squeezes a second lifetime into the first, and if he arrives as a child, he grows up in a hurry. Not so with the exile, whose life creeps forward an inch at a time. If the immigrant rushes, the exile waits. He waits to embark on a new career, to learn the language, to give up his homeland. If immigration is an accelerated birth, exile is a state that looks every bit like a slow death. For the exile, every day is delay, every day is deferral. If his life were a painting, it would be a tableau. If his life were a symphony, it would be played lentissimo. My father waited for forty-two years. He is waiting still. La paja for Alberto Hernández Chiroldes It’s curious – maybe not – how people, even friends, even your brother, avoid you. You call with the news because you want them to hear it from the horse’s mouth. You explain in your best bolero voice, the one the students always fall for, that it’s all right, you’re not going to die. As soon as it’s polite, sometimes sooner, they change the subject. Two months go by and they don’t call back. Meanwhile, between trips to the gym and the john, you marvel at how many men don’t have prostate cancer. You’ve read in all the books – those cheerless manuals of macho woe – that if a man lives long enough, he’11 get it. But you don’t know anyone who’s had it other than your father, who never knew he had it. You’re an epidemic of one, that rare victim of an exceedingly common disease. Disbelieving the medical men, you evolve your own theory about the cause of prostate cancer: masturbation, la paja. You thought you had escaped with zitty cheeks, a slight loss of hearing and eyeglasses. But no. Like an insect that bites with its tail, la paja saved its worst for last, stinging deep inside you, where scalpels barely reach. The Tongue Surgeon for René Prieto  Illness

in a foreign language: There’s more to this than having to

discuss the diagnosis and treatment with physicians named Johnson ar

Sandler who cannot reassure you in the only language in which

reassurance is truly possible. Illness

in a foreign language: There’s more to this than having to

discuss the diagnosis and treatment with physicians named Johnson ar

Sandler who cannot reassure you in the only language in which

reassurance is truly possible.There’s something to this about the imbrication of body and language, organ and word. A tongue is both organ and word. When I was thirteen, a couple of years after arriving in the States, I began to get mouth sores, aftas. I still get them, mostly on my tongue. That’s what I’m talking about. Prostate is a tough word: tough on my tongue, tough on my eyes. Talking to myself, I say próstata, próstata, but it’s not my próstata but my prostate that was removed. Surgeons cannot cut out what they cannot pronounce. I am a tongue surgeon. I operate on my tongue, with my tongue. This is not my tongue. My Own Private Cuba for José Quiroga Over the last four decades, demographers have repeatedly counted the number of Cubans who live in Miami. But has anyone ever counted the number of Cubans who have died in Miami? Has anybody  taken a census of the city’s Cuban dead? Miami is a

Little Havana not because of the Cubans who live there, but because,

perhaps primarily because of those who have died there. The living can

always move away. It’s the dead who are a city’s truly permanent

residents; for once they stop living there, they never stop living

there. Every exile in Miami could go back to Cuba and for me the city

would remain as Cuban as it is today. Hundreds of thousands of exiles

like my father, my grandmothers, my aunts and uncles, have made it so. taken a census of the city’s Cuban dead? Miami is a

Little Havana not because of the Cubans who live there, but because,

perhaps primarily because of those who have died there. The living can

always move away. It’s the dead who are a city’s truly permanent

residents; for once they stop living there, they never stop living

there. Every exile in Miami could go back to Cuba and for me the city

would remain as Cuban as it is today. Hundreds of thousands of exiles

like my father, my grandmothers, my aunts and uncles, have made it so.Now that my father is dead, driving around Miami has become painful. The whole city has turned into a graveyard: Calle Ocho, Bird Road, Miracle Mile. I go into the Publix in Coral Gables and everyone looks older. The men my age are gray and sagging. The once spry viejitos can barely walk. In every old Cuban I look for my father. He’s them, and not them. He’s there, and not there. The names in the cemetery of my own private Cuba: Abuela Constantina, Abuela Martínez, Goyita, Joseíto, Tío Pepe, Tía Josefina, Tía Mary, Tío Mike, Tío Richard, Tío Pedro, Tía Ampa, Tía Cuca, Papi, Papi, Papi. Ashes for Ana María Hernández The afternoon my father died, my mother said that he wanted to be cremated and have his ashes  taken back to Cuba. She claims

that there

are people in Miami who will fly over our dearly beloved island and

scatter his ashes. I find this hard to believe. Only a few years

earlier the two of them had bought plots in the same cemetery where my

grandmother and other family members are buried. Now my mother, a

strict Catholic, also says that she would like to be cremated. I

suspect that at some point they had to sell the plots to pay off my

father’s bookie. taken back to Cuba. She claims

that there

are people in Miami who will fly over our dearly beloved island and

scatter his ashes. I find this hard to believe. Only a few years

earlier the two of them had bought plots in the same cemetery where my

grandmother and other family members are buried. Now my mother, a

strict Catholic, also says that she would like to be cremated. I

suspect that at some point they had to sell the plots to pay off my

father’s bookie.I wish I had known my father as my son knew him. As Abuelo rather than Papi. At the funeral, David was disconsolate. Motioning toward heaven with his hand, the priest said that my father was now resting “up there.” David whispered in my ear that it wasn’t true. One day he would go to Cuba and stand by the almacén Abuelo used to own and look up – and my father would be there, in the Cuban cielo. I have asked what has happened to my father’s ashes. Nobody knows, not even my mother. Ceniza somos, sin fénix. A Radical Cubadectomy for Enrico Mario Santí  I thought my exile ended the day my father died. It

didn’t. Then I thought my exile ended the day of the operation – padre, patria, and próstata bundling together

in my mind, as if father and fatherland converged on that little island

of gland that was cut from my body. It didn’t. I thought my exile ended the day my father died. It

didn’t. Then I thought my exile ended the day of the operation – padre, patria, and próstata bundling together

in my mind, as if father and fatherland converged on that little island

of gland that was cut from my body. It didn’t.Then I had concurrent dreams: In one dream I relived the operation, and as I was about to go under my surgeon left the room and another doctor, whom I had never seen, replaced him. Panic. In the other dream I was talking to an American sailor who had witnessed the Bay of Pigs fiasco. Anger. But no matter what I dream, every morning I wake up with the same question: Will today be the day? Then I switch on the radio ar the TV and find out that no, today is not the day, Fidel Castro hasn’t died or been thrown out yet. I’ve been waking up with the same question for more than forty years. Imagine asking the same woman every morning whether she loves you and always having her answer, as she turns her lovely back to you, “No, not yet, not yet.” Sometime in 1949 I stumbled upon Cuba. I have been stumbling ever since. Dissing the Des- Des-tierro, des-madre, des-cuerpo: exile, divorce, cancer. Exile is destierro, the loss of your homeland or tierra. Divorce is desmadre, an unmothering, but also a slang term for all hell breaking  loose. Descuerpo, my made-up word, names the disruption

of the body (cuerpo) that

cancer brings about. A malignancy is a foreign body, but the truth is

that the foreignness of the tumor transforms one’s whole body, which

becomes foreign too. loose. Descuerpo, my made-up word, names the disruption

of the body (cuerpo) that

cancer brings about. A malignancy is a foreign body, but the truth is

that the foreignness of the tumor transforms one’s whole body, which

becomes foreign too.While I play with words, my stepdaughter is in labor. So what am I doing – my father would have said, ¿qué carajo estás haciendo? – holed up in my study trying to think out ar out-think disease when something so vital, so beneficent, so healthful, is happening clase to me? Forget about Gleason scores and Partin tables. Forget about recurrency rates and survival statistics. Forget about your father. (Yes, your father.) Forget about Cuba. (Yes, Cuba.) Leave your study and enter the birthing room. This is no time for prefixes! Naked nouns sustain: cuerpo, tierra, madre. |